These education modules are for any staff member working within an interprofessional collaborative team caring for patients, resident or clients.

The goal of these learning modules is to complement and supplement present knowledge and support attitudes, skills, and behaviours to be effective team members and leaders within an interprofessional (IP) collaborative patient centred care team.

Module 1 and 2 (Introduction Module and Role Clarity module are to be taken together). After taking the two online modules, you will attend a classroom education session that will further expand on the concepts learned in the online modules.

There are three further online modules followed by 3 separate classroom sessions also.

Staff is requested to only take the module pertinent to an upcoming education session in a classroom setting in order to maximize knowledge.

This education offering consists of 5 modules:

Introduction

no one profession, working in isolation, has the expertise to respond adequately and effectively to the complexity of many service users’ needs

(CAIPE, 2008)

Interprofessional practice / collaboration (IPP/IPC) are not a new concept to some. For others it may be. This module discusses person centred care and the importance of communicating effectively in interprofessional teams. It is the first of 5 modules developed to enhance staff knowledge about interprofessional practice / collaboration.

Acknowledgement

Appreciation and thanks is extended to the following for permission to use content from their documentation to produce this Introductory Module on interprofessional collaboration/practice.

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. A National Interprofessional Competency Framework (2010).

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative: Resources toolkit. Copyright ©2009 All rights reserved.

- College of Health Disciplines and the Interprofessional Network of BC. The BC Competency Framework for Interprofessional Collaboration. © The University of British Columbia, all rights reserved.

- Healthcare Provider’s Practice Toolkit (September, 2010). The Enhance Ontario Project. Toronto, ON. HealthForceOntario.

- Mid Atlantic Renal Coalition. Communication Training Modules.

Thank you is extended to Kelly Lackie (BScN MN PhD(c) RN; Faculty/Interprofessional Education Lead, RN Professional Development Centre, Halifax, Nova Scotia) for reviewing the on line modules.

In this module “Client ” means Patient / Resident / Person

Learning Objectives

On completion of this module:

- Participant will be able to describe what interprofessional collaboration and interprofessional practice is.

- Participant will have increased understanding of what the competencies for Interprofessional Collaboration are according to the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC).

- Participants will have improved understanding of person centred care.

- Participants will have enhanced understanding of the importance of effective interprofessional communication.

What is Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC) and why is it important?

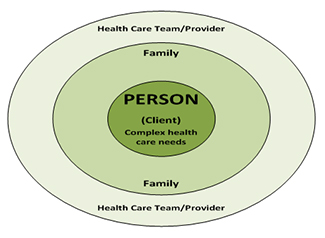

The Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) defines IPC as “the process of developing and maintaining effective interprofessional working relationships with learners, practitioners, patients/clients/ families and communities to enable optimal health outcomes” (CIHC, 2010, p. 6). The “PERSON” (patient/client /resident) is the focus – the reason for the formation of the team and is a full member of the team to the degree that they wish to be.

IPC is not a new term or way of thinking. In 1978, the World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledged that all health care workers needed to be trained to function as a team in order to respond to the health needs of the population as a whole (WHO, 1978).

Patient centered care was also at the center of attention as WHO suggests that individuals have the right and duty to be involved in the planning and implementation of their care (WHO, 1978).

In 2000, the Institute of Medicine released the comprehensive report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which outlined the serious problem of healthcare associated error. In the US, these errors were equivalent to the number of deaths that would be caused by a 747 jet falling from the sky every day. In 2004, the Canadian Adverse Events study was released and indicated that 7.5% of all hospital admissions in Canada resulted in patient harm. This estimate did not extend to clients not admitted to hospitals and served in other care settings, so numbers may actually be higher. Further examination determined that large numbers of these errors could be prevented by improvements in communication and collaboration between providers (Kohn et al, 2000).

Evidence indicates that a lack of communication and collaboration between health providers can seriously harm patients(CIHC,2008,p.7)

What are some of the core concepts related to Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC)?

D’Amour et al., (2005) describe four core concepts that are commonly related to collaboration: sharing, partnership (teaming), interdependency, and power.7(p.8)

| Sharing |

|

| Teaming |

|

| Inter-dependency |

|

| Power |

|

The concept of Sharing includes the following: shared responsibilities, shared decision making, and a shared healthcare philosophy. Other effective strategies include shared values, data, planning and intervention, and professional perspectives.

Teaming (called partnership by D’Amour et al., 2005) implies two or more individuals (or organizations) who share a common set of goals and responsibilities for specific outcomes. A team is characterized by a collegial-like relationship that is authentic and constructive. Team relationships demand open and honest communication. Members treat each other with mutual trust and respect. Members must also be aware of, and value, the contributions and perspectives of the other team members.

Interdependency implies mutual and reciprocal reliance and dependence among all members of the care team that is characterized by a common desire to address each client’s needs. As a client’s need becomes more complex, expertise, contribution and participation is required from each member of the team. As a team works together and ‘gels’, the output of the whole becomes larger than the sum of the individual parts. The synergy then leads the team to collective action.

The fourth concept is Power. In an effective collaboration, power is shared among team members and characterized by “the simultaneous empowerment of each participant whose respective power is recognized by all...furthermore, such power is based on individual knowledge and experience rather than on functions or titles”. (D’Amour et al., 2005, p. 119 (as cited by 7)

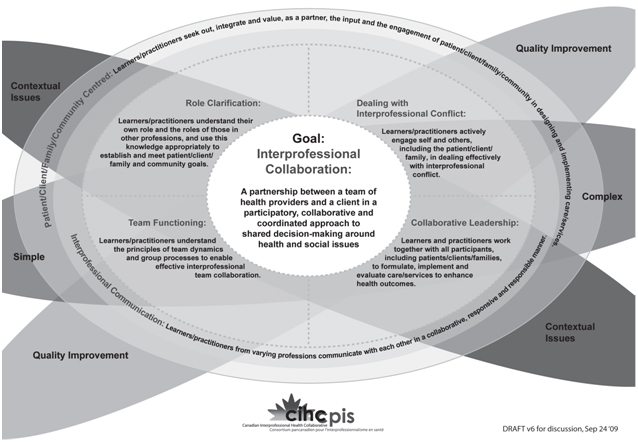

What are the competencies for Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC)?

In 2010, the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) released a framework outlining six specific competencies for IPC. Although these competencies are specific to individuals practicing in healthcare settings and the community, they can also be more broadly applied to organizations focusing on enhanced collaborative processes. The six competency domains are (CIHC, 2010):

- Interprofessional communication

- Person (Patient/Client/Family) - centred care

- Role clarification

- Team functioning

- Collaborative leadership

- Interprofessional conflict resolution 7 (p.9)

National Interprofessional Competency Framework

Interprofessional Collaboration

For interprofessional teams of learners and practitioners to work collaboratively, the integration of role clarification, team functioning, collaborative leadership, and a person-centred focus to care/services is supported through interprofessional communication.3

What is person-centred care?

According to the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC), 2009, person-centred care means that the patient/client (and their family, if applicable) is at the centre of their own health care.

Practicing person-centred care involves listening to clients and families and engaging them as a member of the healthcare team to the level of the client’s desire and comfort in making decisions. When the client is at the centre, the healthcare system revolves around their needs rather than the needs of healthcare providers, fiscal pressures or space allocation. However, person-centred care does not mean clients get exactly what they ask for, but rather that clients are working with their healthcare providers to determine health goals that are realistic, achievable and result in the best possible outcome for the client.

Person-centred care requires a balance between the professional knowledge of health care providers and the personal knowledge of the client and their family. Practicing person-centred care ensures the client is listened to, valued, and engaged in conversation and decision-making about their personal health care needs. It focuses on the client’s goals and the professional expertise of the team and adds the knowledge of all team members to the person’s self-knowledge and self-awareness.4

Providing person centred care in an interprofessional collaborative practice

According to Orchard (2010) interprofessional patient-centred collaborative practice is ”a partnership between a team of health professionals and a patient where the patient retains control over his/her care and is provided access to knowledge and skills of team members to arrive at a realistic team shared plan of care and access to the resources to achieve the plan” (p.249). An interprofessional collaborative practice offering person centred care does not mean that all the health care providers have to be present at all times. The most appropriate person will work with the client at the most appropriate time and ensure access and consultation between the patient and other collaborative team members when required.

Benefits of person centred care to staff and the client

| Benefits to Health Care Staff | Benefits to Client |

|---|---|

| Better health outcomes. (Research shows that the best results, as measured by adherence and outcome, come from a person who is informed and involved.) | Improved person-care outcomes. |

| Increased compliance of the client. | Increased self esteem of the client. Feeling better about themselves. |

| Fewer misunderstandings between the client/staff and staff. | Empowerment of the client to care for, and about, themselves. |

| Staff is more attentive. | |

| Staff is more understanding. | |

| Greater involvement of family and support system in the client’s care.7 |

| Medical Model | Person-Centered Model |

|---|---|

| Person’s role is passive (The client is quiet) | Person’s role is active (The client asks questions) |

| Person is recipient of treatment (The client doesn’t voice concerns, even if there’s a problem) | Person is a member of the team. |

| Provider (usually a doctor) dominates as decision-maker (The provider does not offer options) | Provider, who is based on the person's care needs, collaborates with the person (client) in making decisions. (The provider offers options and discusses pros and cons) |

| Disease-centered | Quality-of-life centered (The client focuses on family and other activities) |

| Provider does most of the talking (The provider may not allow time for questions) | Provider listens more and talks less (The provider allows time for discussion) |

| Person complies (or not) | Person (client) adheres to treatment plan (or not)8 |

Person: means client/patient/resident

Interpersonal & Communication Skills

To practice as a collaborative team practicing person centered care, effective communication is paramount.4

Effective interprofessional communication is dependent on the ability of teams to deal with conflicting viewpoints and reach reasonable compromises.2

Effective interprofessional communication requires the following of the team members:

- Consistently communicates sensitively in a responsive and responsible manner, demonstrating the interpersonal skills necessary for interprofessional collaboration.

- Effectively expresses one’s own knowledge and opinions to others involved in care.

- Demonstrates confidence and assertiveness to express one’s views respectfully and with clarity.

- Employs language understood by all involved in care and explains discipline specific terminology.

- Explains rationale for opinions.

- Evaluates effectiveness of communication and modifies accordingly.

- Actively listens and shows genuine interest in the perspectives and contributions of all team members.

- Is observant and respectful of non-verbal as well as verbal communication.

- Confirms that one understands all ideas and opinions expressed.

- Uses information systems and technology to exchange relevant information and keep team members updated in order to improve care.

- Is aware of and uses information resources from other professions.

- Plans and documents care on a shared health record.

Healthcare professionals are increasingly aware that interprofessional collaboration and effective team communication are essential for improved patient care and safety.1

A three-hospital study by Gawande et al. 2003 (as cited by 10) found that communication breakdowns between health professionals were responsible for 43% of surgical errors (p.351).

A growing body of descriptive and correlation evidence suggests that error rates are unnecessarily high (Baker et al., 2004; Tam et al., 2005), and highlight a relationship between poor communication between health professionals and poor patient outcomes (Alvarez & Coiera, 2006; Gawande et al., 2003; Risser et al., 1999)(as cited by 10,p.351).

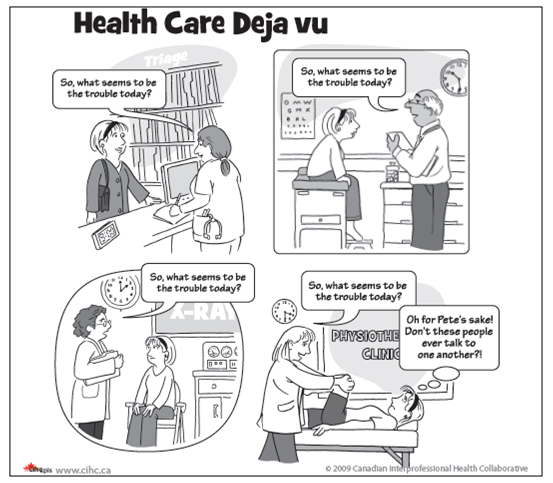

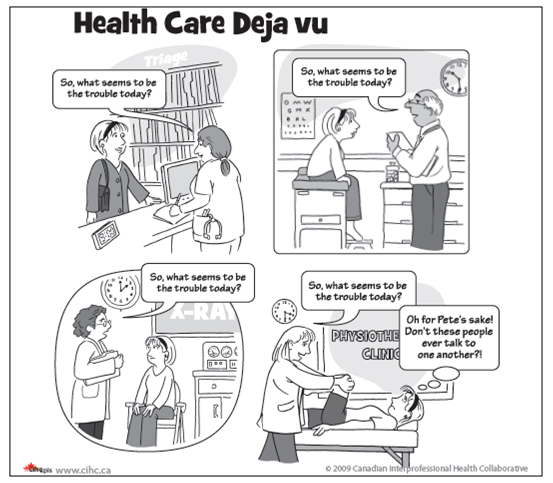

The illustration below demonstrates why we need to communicate with each other. Lack of communication between health care providers does not instil confidence.5

© 2008 Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative.

Person centred care and interprofessional communication are inter-woven into the remaining four competencies. Please review the education modules on the remaining competencies.

References

- Bajnok, I., Puddester, D., Macdonald, C. J., Archibald, D., & Kuhl, D. (2012). Building positive relationships in healthcare: Evaluation of the teams of interprofessional staff interprofessional education program. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal For The Australian Nursing Profession, 42(1), 76-89. doi:10.5172/conu.2012.42.1.76

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. (2010). What is collaborative practice? IP Competencies - Interprofessional Practice Guide - Library and Academic Services at RRC Polytech

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. (2010). A National Interprofessional Competency Framework. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Des_mznc7Rr8stsEhHxl8XMjgiYWzRIn/view

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. (2009). What is patient-centred care? Retrieved from http://www.cihc-cpis.com/uploads/1/2/4/7/124777443/cihc_factsheets_pcc-2010.pdf

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. (2008). Knowledge transfer and exchange in interprofessional education. Synthesizing the evidence to foster evidence based decision making.

- College of Health Disciplines, and the Interprofessional Network of BC. (2008). The British Columbia Competency Framework for Interprofessional Collaboration. Retrieved from http://www.chd.ubc.ca/teaching-learning/competency/bc-framework-interprofessional

- Healthcare Provider’s Practice Toolkit (September, 2010). The Enhance Ontario Project. Toronto, ON. HealthForceOntario. Retrieved from https://odha.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ENHANCE-Providers-Practice-Toolkit.pdf

- Mid Atlantic Renal Coalition (n.d.) Communication Training Modules: Module 2 Patient Centred Care p.4+p.14.

- Orchard, C. (2010). Persistent isolationist or collaborator? The nurse's role in interprofessional collaborative practice. Journal Of Nursing Management, 18(3), 248-257. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01072.x

- Rice, K., Zwarenstein, M., Conn, L., Kenaszchuk, C., Russell, A., & Reeves, S. (2010). An intervention to improve interprofessional collaboration and communications: a comparative qualitative study. Journal Of Interprofessional Care, 24(4), 350-361. doi:10.3109/13561820903550713

- World Health Organization. (1978). Declaration of Alma-Ata.

Proceed to the Role Clarity Module.

Introduction

This module and the education session in the classroom are provided to help individual health care providers clarify their role within the interprofessional collaborative team.

It is important for all health care providers to be aware of the different roles of each health care provider on a team, to learn about their individual perspectives and responsibilities for patient, client, resident care and to recognize and value the potential for role overlap.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation and thanks is extended to the following for permission to use content from their documentation to produce this module on Role Clarity.

- Baycrest: Baycrest Toolkit for interprofessional education and care.

- Building a Better Tomorrow Initiative (BBTI). An Atlantic Provincial Primary Health Care Initiative. (Health P.E.I. Copy, 2009): Team Building: Facilitators Manual.

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. A National Interprofessional Competency Framework (2010).

- College of Health Disciplines and the Interprofessional Network of BC. The BC Competency Framework for Interprofessional Collaboration. © The University of British Columbia, all rights reserved.

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, D.C.: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

- Winnipeg Regional Health Authority: Competency #2 Role Clarification.

Thank you is extended to Kelly Lackie (BScN MN PhD(c) RN; Faculty/Interprofessional Education Lead, RN Professional Development Centre, Halifax, Nova Scotia) for reviewing the on line modules.

In this module “Client ” means Patient / Resident/ Person

Learning Objectives

On completion of this module participants will have increased their knowledge of:

- Role Clarification.

- The Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) competency statement on role clarification.

- How role clarity works in the interprofessional collaborative team?

- The importance of understanding role clarity as a component of interprofessional collaboration.

- Potential members of the interprofessional collaborative team.

- The value that a variety of health care professionals contribute to the interprofessional team.

What is Role Clarification?

Health care providers must consider the roles of others; when working as part of a larger healthcare team. Along with understanding and describing their own roles, health care providers should be able to describe the roles and responsibilities of other health care providers.

When health care providers understand their role and are able to work to their full scope of practice it allows for the utilization of the most appropriate practitioner, provides a fair distribution of the workload and results in effective team functioning (CIHC, 2010). This understanding helps avoid duplication, improves team work and ensures more effective planning, implementation and evaluation of services.8

Role Clarification

Competency Statement: Health care providers, understand their own role and the roles of other health care providers, and use this knowledge appropriately to establish and achieve client / family and community goals.3

Competency Descriptors: Inter professional collaborative team members who understand and value the unique roles and responsibilities of various members of their health care team will demonstrate the following:

- Have sufficient confidence in and knowledge of one’s own discipline to work effectively with others in order to optimize client care;

- Demonstrates ability to share discipline specific knowledge with other health care providers;

- Negotiates actions with other health care providers based on one’s own role constraints and discipline specific ethical and legal practices;

- The ability to access other’s skills and knowledge appropriately through consultation;

- Recognizing and respecting the diversity of other health and social care roles, responsibilities, and competencies;

- The ability to perform their own roles in a culturally respectful way, and be able to shares one’s professional culture and values to help others understand one’s own point of view.

- Respects other team members’ professional culture and values in order to understand their point of view.

- Actively seeks out knowledge regarding others’ scopes of practice;

- Understands how others’ skills and knowledge compliment and may overlap with one’s own;

- Negotiates actions with other health care providers based on an understanding of other disciplinary role constraints, overlap of roles and discipline specific ethical and legal practices and;

- Integrating competencies/roles seamlessly into models of service delivery.3,5

Explanations / Rationale

Role clarification occurs when health care providers understand their own role and the roles of others and use this knowledge appropriately to establish and achieve client and family goals. Health care providers need to clearly articulate their roles, knowledge, and skills within the context of their clinical work. Each must have the ability to listen to other providers to identify where unique knowledge and skills are held, and where shared knowledge and skills occur. To be able to work to their full scope of practice, individuals must frequently determine who has the knowledge and skills needed to address the needs of clients to allow for a more appropriate use of health care providers and a more equitable distribution of workload.3

How does role clarity work in the interprofessional collaborative team?

Members of the interprofessional collaborative health care team recognize and respect the roles, responsibilities and/or competencies of all other team members. They:

- Respect the cultures of their community;

- Use appropriate language to communicate their roles, knowledge, skills, attitudes and judgement;

- Consult with others in appropriate ways to access their skills and knowledge; and

- Build professional and interprofessional competencies and roles in service delivery.

Demonstration of Role Clarification in Action

Following a serious road accident, several injured people are rushed to the emergency department (ED). The ambulance team has provided paramedical services, and now the ED team takes their reports and continues care. Injuries are severe, fatalities have occurred and the ED team is working at full capacity to manage this crisis. Physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, social workers, spiritual care providers, housekeeping staff, porters and department clerks all need to be involved. Each team member must communicate effectively throughout the crisis while understanding how their roles complement or overlap one another. For example the social worker may need to collaborate with the spiritual care provider throughout the emergency stay so that the best possible treatment and support is provided.8

Learning about Roles & Responsibilities is key to collaboration

Learning about other professions is an important first step in collaboration. Many health care providers are unaware of the other health professions role due to a lack of collaboration during their respective education. In the course of their training, health care providers have a tendency to become socialized into their own professions and subsequently develop negative biases and naïve perceptions of the roles of other members of the health care team.

To practice effectively in an interprofessional health care team, however, one must have a clear understanding of other providers unique contributions: their educational backgrounds, areas of high achievement, roles, responsibilities and limitations.

Teamwork in a health care setting involves considerable overlap in competencies. Each health care provider should be knowledgeable of (and therefore comfortable with) the skills of the other health care providers. Moreover, an often overlooked member of the health care team is the client as well as their family. Health care providers must understand that the client and their family are integral members of the health care team with roles and responsibilities of their own.

From a clear understanding of others comes the basis for respect which underlies all successful collaborative endeavours. The need to establish the trust and respect of other team members derives from a central feature of collaboration:

No individual is responsible for all aspects of the client’s care, and therefore each member must have confidence that other team members are capable of fulfilling their responsibilities.2

Each health care provider's roles and responsibilities vary within legal boundaries; actual roles and responsibilities change depending on the specific care to be delivered. Non regulated team members roles and responsibilities vary depending on their work site. Health care providers may find it challenging to communicate their own role and responsibilities to others. For example, Lamb et al (2008) discovered that staff nurses had no language to describe the key care coordination activities they performed in hospitals. Being able to explain what other health care providers’ roles and responsibilities are and how they complement one’s own is more difficult when individual roles cannot be clearly articulated. Safe and effective care demands clearly defined roles and responsibilities.

Collaborative practice depends on maintaining expertise through continued learning and through refining and improving the roles and responsibilities of those working together.6

Why is it important to clarify skills, roles and responsibilities?

Health care providers from different disciplines/job categories are educated in their own unique professional environment and culture with its own language, terminology, problem-solving methods, behaviours, values and beliefs.

Because of this, many health care providers may not be familiar with the education base, the roles, or the range of functions of providers of other disciplines/job categories. This unfamiliarity with others can lead to under-utilization of skills and capabilities and to disputes about areas of overlapping practice within a team. Sometimes there is disagreement because the expectations and language create confusion.

Interprofessional collaborative team members from different disciplines bring a unique set of skills. Each member of the team needs to understand the unique expertise contributed by each member and the areas where knowledge and skills overlap. This understanding will contribute to mutual respect. Recognizing this overlap in competencies will help an interprofessional collaborative team determine who does what. By knowing the skills of other health care providers, team members can also refer clients more appropriately.

Failure to establish clarity of roles and to take advantage of the complementary skills of all team members can lead to frustration, conflict and inefficiency in service delivery.

To establish effective collaboration, it’s important to ensure that each provider on the team understands the role, scope of practice/employment and experiences of other health care providers in the team, and has the ability to articulate their own unique contributions.

A team focus identifies the clients problems from a holistic perspective:

- Medical issues and treatments

- Psychological/emotional issues and treatments

- Social issues and treatments

- Economic issues and treatments

- Living conditions and treatments7 (as cited by 1)

The client is central to any team

The need to address complex health promotion and illness problems, in the context of complex care delivery systems and community factors, calls for recognizing the limits of professional expertise and the need for cooperation, coordination, and collaboration across the professions in order to promote health and treat illness. However, effective coordination and collaboration can occur only when each profession knows and uses the others’ expertise and capabilities in a patient-centered way.

What do the Health Professionals on your team do?

Here are some examples of members of a collaborative team and their roles.

*This is not an all inclusive list*

| Team Member | Role and Responsibility |

|---|---|

| Dietitian |

Dietitians are food and nutrition experts who translate scientific, medical and nutrition information into practical individualized therapeutic diets and meal plans for people. They work with a variety of health professionals to manage nutrition for health promotion, disease prevention, and treatment of acute and chronic diseases. College of Dietitians of Ontario1 |

| Licensed Practical Nurse | A licensed practical nurse provides support and nursing services to clients, family members, and the community. According to the Canadian Council of Practical Nurse Regulators, “LPNs assess, plan, implement and evaluate care for clients throughout the life cycle and through palliative stages”. College of Health Disciplines British Columbia5 Licensed Practical nurses are most efficiently utilized in caring for patients with predictable (identified, unchanged, predictable) challenges and /or known health outcomes.10 |

| Medical laboratory technologist | Medical laboratory technologists perform lab tests on blood, body fluids, cells and tissues. MLTs in various specialties collect and process specimens, analyze results, and interpret findings. The knowledge and expertise of the MLT contributes to innovation in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of diseases and medical conditions. The College of Medical Laboratory Technologists of Ontario (CMLTO)1 |

| Medical radiation technologist | Radiological technologists aid in the diagnosis of disease and injury by producing permanent images which are read by a physician who specializes in radiology. These images are captured on X-Ray film and other imaging devices such as video monitors, video tape and electronic digital imaging devices. The College of Medical Radiation Technologists of Ontario (CMRTO)1 |

| Occupational therapist (OT) | Occupational therapists help clients learn or re-learn to manage the everyday activities that are important to them, including caring for themselves or others, caring for their home, participating in paid and unpaid work and leisure activities. Occupational therapists address not only the physical effects of disability, injury or disease but also the psychosocial, community and environmental factors that influence function. College of Occupational Therapists of Ontario11 |

| Pharmacist | Pharmacists are experts in medication management. They are responsible not only for obtaining and dispensing medications, but also for their safe and effective use in the prevention of disease and the promotion of health and wellness. Ontario College of Pharmacists1 |

| Physician | Physicians assess the physical or mental condition of an individual and the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of any disease, disorder or dysfunction. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario1 |

| Personal Care Worker (PCW) | PCWs do what a client would do for him or herself if physically and/or cognitively able. The role of a PCW depends upon the individual needs of the client, but can include home management, personal care, family responsibilities (routine care giving to children), and work, social and recreational activities. No regulatory body: For more information, visit Personal Support Network of Ontario1 |

| Physiotherapist (PT) | Physiotherapists are experts in physical rehabilitation. Physiotherapists assess physical function and treat, rehabilitate and prevent physical dysfunction, injury or pain, to develop, maintain, rehabilitate or augment function or to relieve pain. They assess the patient, establish a diagnosis for physical dysfunction, and then plan and implement an appropriate treatment program. College of Physiotherapists of Ontario1 |

| Registered Nurse | A registered nurses competency is based on five categories: professional responsibility and accountability, knowledge-based practice, ethical practice, service to the public, and self-regulation. Registered nurses promote health and the assessment of, the provision of care for, and the treatment of health conditions by supportive, preventive, therapeutic, palliative and rehabilitative means in order to attain or maintain optimal function. College of Nurses of Ontario1 Registered Nurses (RNs) are most efficiently utilized in caring for patients with complex (new, changed or complex) challenges and/or unknown health outcomes.10 |

| Respiratory Therapist | According to the “CSRT” Respiratory Therapists possesses a specialized body of knowledge, and base the performance of their duties on respiratory therapy theory and practice. They are essential members of the healthcare team, and assume a variety of roles in different areas of practice, such as clinical, education, health promotion, management, research, administration, and consulting. Respiratory therapists practice independently, interdependently, and collaboratively, and may practice within legislated professional regulations.9 |

| Social worker | In an interdisciplinary team, social workers provide the psychosocial perspective to complement the biomedical perspective. Social workers assess, diagnose, treat and evaluate individual, interpersonal and societal problems through the use of social work knowledge, skills, interventions and strategies, to assist individuals, families, groups, organizations and communities to achieve optimum psychosocial and social functioning. Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers1 |

| Speech-language pathologist (SLP) | SLPs prevent, identify, assess, treat and (re)habilitate communication and/or swallowing disorders. They also provide education and counseling services for people experiencing communication and/or swallowing difficulties. College Of Audiologists and Speech Language Pathologists1 |

| Unregulated health care worker | Contribute to the collaborative team depending on their job description and work site. |

Conclusion

To work in an intercollaborative team, members must understand their role in the team, the role of other team members and where overlap in practice may occur. This understanding will aid communication within the interprofessional collaborative team and will help develop and deliver patient/client centered care. Establishing clarity of roles will allow access to the complementary skills of all team members. This will help prevent frustration, conflict and inefficiency by ensuring the most appropriate person is providing the most appropriate care to the client requiring it.

There is an additional education session in a class room setting to help clarify the importance of appreciating the role that individual team members contribute to overall patient care. Understanding your role and the role of other health care providers is part of the process to function in an interprofessional competent manner. Role clarification will be explored further with other health care providers.

Please complete the online evaluation of this module. On completion you will be e-mailed a continuing education certificate for your continuing education portfolio.

References

- Baycrest, (2012). Baycrest toolkit for interprofessional education and care (IPE/C). Retrieved from https://www.baycrest.org/Baycrest/Education-Training/Centre-for-Learning,-Research-innovation/Our-Programs/Baycrest-Toolkit-for-Interprofessional-Education-a.aspx

- Building a Better Tomorrow Initiative (BBTI). An Atlantic Provincial Primary Health Care Initiative. (Health P.E.I. Copy, 2009): Team Building: Facilitators Manual.

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. (2010). A National Interprofessional Competency Framework. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Des_mznc7Rr8stsEhHxl8XMjgiYWzRIn/view

- College of Health Disciplines., & University of British Columbia. (2008). The British Columbia Competency Framework for Interprofessional Collaboration. Retrieved from http://www.chd.ubc.ca/teaching-learning/competency/bc-framework-interprofessional

- College of Health Disciplines., & University of British Columbia. (n.d.) What types of nurses are there?

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, D.C.: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

- John A. Hartford Foundation Inc. (2001). Geriatric Interdisciplinary Team Training Program.

- Winnipeg Health Region: (2013) . Competency #2: Role Clarification.

- The Canadian Society of Respiratory Therapists. (n.d.) Standards of practice for respiratory therapists. Retrieved from https://www.csrt.com/rt-profession/

- Nova Scotia Department of Health, Professional Practice at Capital Health, College of Registered Nurses (CRNNS), College of Licensed Practical Nurses (CLPNNS) and the Registered Nurses Professional Development Centre (RN- PDC), (2010) Optimized Practice Optimizing the role of the RN, LPN and Assistive Personnel in acute care: A program to support the model of care initiative in Nova Scotia. MODULE: Core Concepts – Participant.

Introduction

This module and the education session in the classroom are provided to introduce participants to the principles, processes, values and techniques underlying effective interprofessional or collaborative teamwork in a health care settings and organization.

The overall goal of the Team Building online module and the classroom education session is to enhance participants’ knowledge, skills and confidence in leading and participating as members of interprofessional teams in health care.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation and thanks is extended to the following for permission to use content from their documentation to produce this module on Team Functioning.

- Baycrest: Baycrest Toolkit for interprofessional education and care.

- Building a Better Tomorrow Initiative (BBTI). An Atlantic Provincial Primary Health Care Initiative. (Health P.E.I. Copy, 2009): Team Building: Facilitators Manual.

- Building a Better Tomorrow Initiative (BBTI). An Atlantic Provincial Primary Health Care Initiative. (Health P.E.I. Copy, 2009): Team Building: Participants Manual.

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. A National Interprofessional Competency Framework (2010).

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, D.C.: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

- University of Manitoba. (Module 3 A; Facilitators Guide. Interprofessional Practice Education in Clinical Settings: Immersion Learning Activities. Appendix 1.

Thank you is extended to Kelly Lackie (BScN MN PhD(c) RN; Faculty/Interprofessional Education Lead, RN Professional Development Centre, Halifax, Nova Scotia) for reviewing the on line modules

In this module “Client ” means Patient / Resident / Person

Learning Objectives

On completion of this module participants will have increased their knowledge of:

- The team functioning competency statement from the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaboration

- The definition of a team?

- Phases of interprofessional collaborative team development

- How to establish an interprofessional collaborative team

- How to evaluate the interprofessional collaborative team

- Circumstances that favour the formation of interprofessional collaborative teams

- Advantages and Limitations of forming interprofessional collaborative team care

- Territoriality

- Key areas that an interprofessional collaborative teams must address

- Tools to improve communication within the interprofessional collaborative team

- Principles of effective interprofessional collaborative team meetings

- Steps to assist the interprofessional collaborative team to assess a client’s needs

Competency Statement on Team Functioning

From the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaboration:

Health care providers understand the principles of team work dynamics and group/team processes to enable effective interprofessional collaboration.

Competency

To support interprovider/interprofessional collaboration, health care providers are able to:

- understand the process of team development

- develop a set of principles for working together that respects the ethical values of members

- effectively facilitate discussions and interactions among team members

- participate and be respectful of all providers’ participation in collaborative decision-making

- regularly reflect on their functioning with team practitioners, the client and their family

- establish and maintain effective and healthy working relationships with health care providers, the client and their family, whether or not a formalized team exists

- respect team ethics, including confidentiality, resource allocation, and professionalism.

Explanation/Rationale

Safe and effective working relationships and respectful inclusion of the client/family are characteristic of interprofessional collaborative practice. Collaboration requires trust, mutual respect, availability, open communication and attentive listening – all characteristics of cooperative relationships. Health care providers must be able to share information needed to coordinate care with each other and each client and their family and to avoid gaps, redundancies, and errors that impact both effectiveness and efficiency of care delivery. Complex situations may require shared care planning, problem-solving and decision making for the best outcomes possible.

In some situations, collaborative practice is undertaken via a formal interprovider/interprofessional team, requiring an understanding of team developmental dynamics, or practice in a micro-system, requiring awareness of how organizational complexity influences collaborative practice. Health care providers need to regularly reflect on their effectiveness in working together and also in achieving or meeting the needs of the client and their family.

Awareness of and commitment to interprofessional ethics unites all health care providers in the common goal of delivering the best care possible to the client, their family, and is fundamental to the ability to work together collaboratively.5

What is a Team?

small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.

Katzenbach, & Smith, 1994. 10 as cited by 3

Team Functioning

Learning about other health care providers is an important first step in collaboration. Many health care providers are unaware of what others “do” due to a lack of collaboration during their respective education. In the course of their training, providers have a tendency to become socialized into their own professions and subsequently develop negative biases and inaccurate perceptions of the roles of other members of the health care team. To practice effectively in an interprovider/interprofessional health care team, however, one must have a clear understanding of other members’ unique contributions: their educational backgrounds, areas of high achievement, and limitations. Teamwork in the health care setting involves considerable overlap in competencies. Each health care provider should be knowledgeable of (and therefore comfortable with) the skills of the other members. Moreover, an often overlooked member of the health care team is the client him- or herself, as well as the client’s family. As a member of the team, the client and other team members can develop the plan of care together. The intercollaborative team must include the client and their family by focusing on person (client) centred care.3

Team delivery of person (client) centred care.

Plan of care goals are developed in consultation with the rest of the team and therefore will be congruent with their expressed values. This requires the health care team to see the person as a full-fledged member of the team and therefore devote time in their assessment actively encouraging the client and their family to express their opinions, social circumstances and belief system. Communication should be open, non-judgmental and respectful and the client/family should be treated like they are an integral part of the interprovider/interprofessional team to the level they are comfortable with and in a supportive environment.

At times the client and/or family depend on the clinical team to guide them on specific and achievable outcomes especially for those decisions requiring clinical expertise and knowledge of diagnosis and treatment options. There are times when the clinical team identifies a problem area which the client/ family has not considered/does not consider a priority. A negotiation then follows between the client, their family and the team as to whether to address this area. If there are issues of client safety e.g. driving ability, financial abuse, the team members may have professional, legal or ethical duties which require them to address this area even if the client/family are not in agreement.

Phases of Interprofessional Collaborative Team Development

In order to help build a team, we need to remember that, like humans, teams develop through a series of stages. Probably the best-known model of team development is that of Tuckman (1965). (12 as cited by 3)

1) Forming

This is the very first stage of team development. Here team members meet for the first time, they determine their purpose, and they orient themselves to each other and the task as well as begin to establish trust between team members.

Key tasks at this stage are:

- to establish the goals of the team

- to learn about the skills and training of other team members

- to develop relationships based on mutual respect and shared goals

2) Storming

A key issue for teams is to effectively manage conflict while avoiding group think (i.e., where everyone blindly follows along and no one asks any questions). It is critical that teams balance both of these elements. Too much conflict can delay performance but too little conflict (i.e., group think) can stagnate creativity. So, in this stage, teams must determine how they will manage conflict, encourage differing views, and challenge the status quo.

Key tasks at this stage are:

- to develop effective means of role negotiation and conflict resolution for the team to progress to the next stage

- to develop methods of identifying problems with the team

- to re-evaluate initial goals, tasks and roles

- developing processes to overcome group think

3) Norming

Here the team starts to determine roles and responsibilities, sets and agrees on goals, develops operating guidelines for team functioning in their meetings and daily tasks, and determines the level of individual commitment needed to achieve the goals of the team.

Key tasks at this stage are:

- to establish the tasks and roles of team members

- to establish the mechanisms of communication

- to determine leadership and decision-making process

4) Performing

Once teams have reached this level, they are well-oiled machines. The key task at this stage is to maintain effective mechanisms for (1) continued communication, (2) conflict resolution, (3) continued goal and role re-evaluation, (4) evaluation of outcomes of team functioning, and (5) making the appropriate adjustments to the team. (13 as cited by 3)

Adjourning is the 5th level of group dynamics & occurs when the group no longer works together 11

A few notes of interest here:

- While scholars agree that teams go through four stages of development, there is some disagreement regarding the order of norming and storming. Some people argue that teams play nice first (i.e., norming) and then the issues of conflict emerge (i.e., storming); others argue that team’s storm first and then determine norms (see Whetten & Cameron for a discussion11). Either way, all scholars agree that all four stages are necessary for teams to be effective.

- Teams will cycle through these stages. Every time a new team member is added, the team will start back at stage 1. Note that teams develop in terms of both task processes and people processes (i.e., relationships) as they move from stage to stage.3

How to establish an Interprovider/Interprofessional Collaborative Team - Step by step guide

Step 1: Determine the Mission/Common Purpose4

- In 2 –3 sentences describes what the team is all about.

- Answer the following questions:

- What is the team’s role?

- Who are the key stakeholders?

- What are the CORE services offered by the team?

- What are the key challenges the team faces?

- The team checks to ensure that it includes members with the skills needed to achieve the purpose. If not, the team must seek out additional team members with the needed skills

Step 2: Performance Goals and Strategies

Based on the mission, have the team set 3-5 SMART goals. These goals must be:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Attainable (Hint: A good goal is difficult enough to challenge the team, but not so difficult that it cannot be attained)

- Relevant to the mission & recorded on paper

- Time-based

- Teams may choose to establish process or strategy goals. In both cases, you can complement longer term goals with shorter-term benchmarks.

Step 3: How will we evaluate and measure our goal progress?

- How is team effectiveness or success measured? Client health & functional status, use of provider time, satisfaction of team members/administrators / the client, costs, missed appointments, use of community emergency department services

- Which elements of the team approach lead to more effective outcomes?

- For which person is the team approach most effective?

- Under what conditions does the team operate most effectively?

Step 4: Determine roles and operating guidelines

The interprofessional collaborative team must determine roles, responsibilities & operating guidelines such as:

- Who is considered part of our team? Who are the team members?

- What are our expectations of each other?

- What is the role of the team leader?

- How does my role affect you?

- How does your role affect me?

- How does my role affect the team?

- How do we affect the person/client?

- How do we conduct effective meetings and how frequently?

- How will we share key information?

- How do we manage virtual team-members?

- How do we deal with conflict and foster an environment where people can present differing views?

- How do we address team members that are not ‘doing the right stuff’ and are hurting the team’s performance?

Step 5: Clear roles & operating guidelines: Why do we need them?

Clear roles and operating guidelines can help minimize the following ineffective interprofessional collaborative team behaviours:

- Team member disagreements

- Key work elements are missed (e.g, “Not my job.”)

- Multiple people doing the same work

- Decisions made in a vacuum (eg. some team members being left out of the decision making process)

- Blame game

- False agreement/group think

- Triangulation (e.g., there is a conflict between two people and they both ‘vent’ the issue at a third person)

Step 6: Create the plan

The final step is to take all the information collected in steps 1-5 and create a team charter. Plan should include sections on:

- Mission/common purpose

- Goals and measurement

- Operating guidelines

- Records of team meetings and decisions

Evaluating the Interprovider/Interprofessional Collaborative Team Process

Participation3

- Did each team member adequately participate in the discussion, contribute to the problem? To the care plan? (Important to take into account that each team member may not contribute to the discussion, or the team in the same way)

- Did team members express themselves clearly?

- Did team members follow-up/ask for clarification on vague comments or positions by others?

- Did the team process business in a way that allowed each member to contribute his or her viewpoint/role?

- Was there leadership to create the necessary structure and organization for the team to complete its business?

- Did leadership change based on needs?

- Was there adequate leadership for creating challenging and analyzing ideas?

Interprovider/interprofessional collaborative teams are established in order to provide collaborative care with client participation to the level they are comfortable with.

Circumstances that favour the formation of interprofessional collaborative teams

- the problems are complex enough to require more than one set of skills or knowledge

- the amount of skills or knowledge is too great for one provider

- assembling a group of health care providers will enhance the solution to the problems

- team-members can communicate on an equal basis

- all providers are willing to sacrifice some provider autonomy in working together for a common goal. (7 as cited by 3)

Principles of effective interprovider/interprofessional collaborative health care teamwork include the following:

- focus of members should be on needs of the client rather than on individual contributions of members;

- the basis of any health care team working collaboratively is communication with the client, a central principle shared by all health care providers;

- collaboration requires both, depending on others and contributing one’s own ideas toward solving a common problem;

- team members must respect, understand roles, and recognize contributions of their members;

- teams work both within and between organizations; (Grant 1995)

- Individuals may have improbable expectations of other team members which can lead to role ambiguity, role conflict, and role overload. (7 as cited by 3)

Advantages of forming an interprovider/ interprofessional collaborative team care

For clients:

- improves care by increasing the coordination of services

- integrates health care for a wide range of health needs

- empowers the client as an active partner in care

- can be oriented to serving clients of diverse cultural backgrounds

- more efficient use of time

For providers:

- increases provider satisfaction due to clearer, more consistent goals of care

- facilitates shift in emphasis from acute, episodic care to long-term preventive care and chronic illness management

- the collaborative experience enables the provider to learn new skills and approaches to care

- provides an environment for innovation

- allows providers to focus on individual areas of expertise

For educators and students:

- offers multiple health care paradigms to study

- fosters appreciation and understanding of other disciplines

- models strategies for future practice

- promotes student participation

- challenges norms and values of each discipline

For health delivery system:

- potential for more efficient delivery of care

- maximized resources and facilities

- decreases burden on acute care facilities as a result of increased prevention and client education interventions. (7 as cited by 3), (Baggs & Schmitt, 1997; Baker & Norton, 2004; Barrett, Curran, Glynn, & Godwin, 2007; Hendel, Fish, & Berger, 2007; Zwarenstein, Reeves, & Perrier, 2005),(as cited by 1)

- 82% of clients felt the quality of their health care experience was significantly improved when delivered by an interprovider/interprofessional team.6

Limitations of interprovider/ interprofessional collaborative team care

- process of team formation is time consuming & requires matching of schedules of different team members

- collaboration requires communication between team members, which takes time away from the client’s appointment in busy practices

- a comprehensive approach to health care may lead to increased use of limited services and resources

- a successful team requires on-going conflict resolution and goal re-assessment; failure of these tasks may impair health care delivery

- the interprovider/interprofessional collaborative team must also address issues of territoriality (7 as cited by 3)

Territoriality

A barrier to interprofessional collaborative teamwork is the problem of “turf battles.” These struggles over protecting the scope and authority of a profession involve issues of autonomy, accountability, and identity.

The principle of autonomy reflects the desire for each profession to define itself, to set its own criteria for practice and professionalism, and to maintain sole influence over its area of expertise. Loss of autonomy may lead to undesired changes in modes of practice and to loss of potential earnings.

Accountability, another key component of professionalism, refers to the evaluation and assessment of standards of care. Health care providers both define how they want to practice and are accountable to others in their profession for practicing according to these standards. Collaboration introduces performance evaluation by team members from other professions, which for some individuals represents an invasion into their own professional domain.

Finally, identity as an individual practitioner is due in large part to the identity of the profession as a whole. Interprofessional collaboration, by blurring the margins that define the roles of the various professions, may also impact upon the identity of individual providers.3

The task of the collaborative enterprise is to identify and address these underlying factors that lead to territoriality and to thereby facilitate interprofessional collaboration.

Key areas that interprovider/ interprofessional teams must address

1) Integrated clinical care

- health care providers contribute co-ordinated decision-making and management skills

- division of labour is organized around common goals, and provider competencies with each provider contributing his or her expertise as needed

- outcomes and goals are regularly re-evaluated

- health care providers share responsibility for the client’s care, including shared responsibility for positive and negative outcomes

2) Open communication

- Client case discussions involve not only diagnosis and management, but also individual and family issues.

- the client and their family are actively involved in the discussion of care and are considered team members

- pathways of communication are ensured by the organizational structure

Healthcare providers can learn to communicate with each other, with the client, in ways that are effective and meaningful. This in turn, will lead to a reduction in harm, increased satisfaction for all providers and overall better outcomes for the client and their family.

If there were one aspect of health care delivery an organization could work on that would have the greatest impact on client safety, it would be improving the effectiveness of communication on all levels – written, oral, electronic .

(Croteau, JCAHO)

3) Providers trained in team concepts

- collaborative rather than delegative model is employed;

- team members have skills in communication, conflict resolution, and leadership;

- members understand the roles and expectations of others; and

- members are innovative and tolerant of change

4) Respect for other team members

- team members are open-minded and respectful of other disciplines; and

- providers recognize the contributions of other team members (7 as cited by 3)

Key areas the teams must address

Having decided to implement an interprovider/ interprofessional collaborative team model there is a need to navigate the team development phases, and achieve the definition of an effective team.

This requires that teams address several key issues. Moreover, an examination of these five questions can help one understand issues that may be helping, or hindering, the performance of a team. The following summarizes the key areas that teams must address. (7 as cited by 3)

1. What is the team’s direction?

Here the team must establish its common purpose and goals. These are critical as it gives the team a sense of purpose and provides direction. Remember that teams should periodically revisit their common purpose and goals, both to track success as well as to ensure that they are still relevant.

2. Who performs which tasks and with whom?

Here teams must determine the key tasks and who is responsible for which tasks. Remember, teams are made up of people with unique and complementary knowledge and attitudes/judgement and have mutual accountability for the end result. Thus, while health care providers' may have clearly assigned roles, there must be some flexibility here as health care providers will need to ‘pitch in’ and cross traditional role boundaries in order to perform effectively. As such, it may be more beneficial to develop effective ways of sharing some of the responsibilities and tasks rather than only assigning them to a single health care provider. In terms of roles, it is helpful to consider the following:

- role clarity vs. ambiguity (are expectations clearly defined?)

- role compatibility vs. conflict (do roles conflict?)

- role overload (can an individual meet all expectations?)

The decisions of who does what can be guided by provider availability, level of training, or team member preferences. As with the setting of goals, it is important to periodically review and revise team member roles as necessary.

3. Leadership and Decision-Making

An emerging pattern in many health care teams involves equal participation and responsibility on the part of team members with “shifting” leadership determined by the nature of the problem to be solved.

In developing a mechanism for making decisions, the team must address the following questions:

- What needs to be decided?

- Who should be involved in the process? Who has the knowledge, skill and/or attitude/judgement for dealing with the decision?

- What decision-making process should be used?

- Who will be responsible for carrying out the decision?

- Who needs to be informed about the decision?

It would be unnecessary to require every member of the team to be present and to contribute to every decision of the team. Clearly, decisions will be made by a subset of team members in a time-efficient manner. Effective decision-making within the context of a collaborative team requires a balance between involving the fewest number of members without compromising the validity of the decision.

4. What mechanisms are needed to facilitate high team performance?

Teams must establish clear guidelines concerning issues such as conflict resolution, sharing of critical information and ensure effective communication within the team.

Conflict Resolution.

Given the mixture of skills and backgrounds, and the complexity of interprovider/interprofessional collaboration, a diversity of views and differences of opinion are inevitable. It is important to recognize, however, that conflict is both necessary and desirable in order for the team to grow and thereby develop greater efficiency and effectiveness.

Sharing of information.

To provide effective, coordinated care, a team must have an efficient mechanism for exchange of information. At the simplest level, this requires the time, space, and regular opportunity for members to meet and discuss individual client cases.

An ideal system for communication would include:

- a well-designed record system

- a regularly scheduled forum for members to discuss management of client issues

- a regular forum for discussion and evaluation of team function and development, as well as related interpersonal issues

- a mechanism for communicating with the external systems within which the team operates

Tools to improve communication within the interprovider/ interprofessional collaborative team

Open lines of communication are necessary to effective teamwork. It is the way that teams achieve their objectives. Research by the Association of Ontario Health Centres, (2007) found that being able to communicate and discuss concerns both formally and informally was important to reducing the stress of the work. Casual face to face encounters provided support and assistance to team members in their roles. And, poor communication was identified as a barrier to resolving conflict.

- Reasonable people can—and do—differ with each other. No two people are the same. Diversity among team members enhances creativity.

- Learn as much as you can from others. Learning the various backgrounds, cultures, and provider values of others can enrich your own skills and abilities.

- Evaluate a new idea based on its merits. Avoid evaluating ideas based on who submitted them or how closely the mirror your own personal preferences.

- Avoid comments and remarks that draw negative attention to a person’s unique characteristics. Humor is a key factor in a healthy team environment but should never be used at the expense of another’s identity or self-esteem.

- Don’t ignore the differences among team members. The differences should be honoured and used to advance the goals of the team.2

Without effective communication, the client is left feeling that health care providers do not speak to each other.

© 2008 Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative.

What is effective communication

Effective communication relies on team members listening and explaining their perceptions, and acknowledging and discussing their differences and similarities in views. Good communication means team members recommend and negotiate appropriate treatments for the person.

Barriers, such as differences in language and culture, can exist among team members and can make it difficult for one member to understand the meanings, intentions, and reactions of other team members. Our cultural heritage, sex, class, education level and stage of life influence our use of language and our perception of others. Team members must be aware of these differences in order to effectively communicate with each other as well as with the client and their family members.

Team members also need to recognize and value the different competencies and approaches of different health care providers. The key to team success is to value the differences on the team and use such diversity to achieve the team’s common purpose. (9 as cited by 2)

Effective healthcare teams are of great importance for meeting client needs, which is only possible through co- ordinated efforts and reliable communication processes (Department of Health, 2001; Husting, 1996). We consider that for this to happen, all members of the healthcare team must be clear of their own and others value, share an identity as a care team and work interdependently – thus implementing an interprovider/interprofessional approach to care 11

The following tips are helpful for valuing diversity and improving communication on your team: (9 as cited by 2)

| Closed questions |

|

| Open questions |

|

| Minimal leads and accurate verbal following |

|

| Repetition |

|

| Paraphrasing and reflecting |

|

| Clarifying responses |

|

| Confrontation and honest labelling |

|

| Integrating and summarizing |

|

Team Meetings

Principles of effective Interprofessional Collaborative Team Meetings

Team meetings can be structured, however a team meeting can be as simple as a unit huddle, two - three health care providers discussing a client’s care in the office, around the quality board when they meet.

Guidelines for interprofessional collaborative team members to aid consensus at meetings

- Contribute to the discussion rather than defend their position

- Seek out win-win solutions that satisfy the needs/concerns of all team members

- Use active listening skills and summarize what others are saying

- Seek to get the rationale for a person’s view

- Avoid voting or averaging to get an answer

- Don’t be afraid to disagree – address your differences in terms of the idea being presented not the person

To ensure consensus on the interprovider/ interprofessional collaborative team, contemplate the following questions

- Has each team member been honestly listened to?

- Have team members listened and understood the views of others?

- Do team members seem supportive of the alternative being discussed?

- Can each person summarize the alternative?

- Has it been a while since any new opinions/views were presented?3

Steps to assist the interprovider/ interprofessional collaborative team to assess the client's needs

The following questions will assist the interprovider/interprofessional collaborative team to assess what whether the clients' needs are being addressed. Considering the client’s medical, emotional, social, environmental and economic needs, answer each of the following questions:

- What is the overarching goal? At least three perspectives need to be considered and reconciled:

- client

- his/her family

- team

2) What are the client’s problems? (e.g. medical, emotional, social, environmental and economic).

3) What is the impact of each problem on the client’s health?

4) What strengths and resources does the client have or can be mobilized to deal with each problem?

5) What additional information is needed to adequately define the problem or its implications?

6)Who is involved in developing the plan of care? (What needs to be done; who will do it; when will it happen?)

7) What outcomes should be expected for each problem? (e.g. expressed in measurable terms, appropriate time to look for the outcomes) (8 as cited by 3)

Conclusion

This module was developed to assist with knowledge of “team functioning” in an interprovider/interprofessional collaborative environment. A definition of what a team is, its characteristics and key principles were supplied. Information of circumstances that favour interprovider/interprofessional collaborative team formation was given and advantages and limitations to team care were mentioned.Each team will be established according to their established need. Suggestions were provided to assist this process. An effective functioning interprovider/interprofessional collaborative team is essential to the delivery of effective care by the right person in the right place at the right time.

There is an additional education session in a class room setting to assist learning about team functioning from and with other health care providers.

Please complete the online evaluation of this module. On completion you will be e-mailed a continuing education certificate for your continuing education portfolio.

References

- Bajnok, I., Puddester, D., Macdonald, C. J., Archibald, D., & Kuhl, D. (2012). Building positive relationships in healthcare: Evaluation of the teams of interprovider staff interprovider education program. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal For The Australian Nursing Profession, 42(1), 76-89. doi:10.5172/conu.2012.42.1.76

- Baycrest, (2012). Baycrest toolkit for interprofessional education and care (IPE/C). Retrieved from https://www.baycrest.org/Baycrest/Education-Training/Centre-for-Learning,-Research-innovation/Our-Programs/Baycrest-Toolkit-for-Interprofessional-Education-a.aspx

- Building a Better Tomorrow Initiative (BBTI). An Atlantic Provincial Primary Health Care Initiative. (Health P.E.I. Copy, 2009): Team Building: Facilitators Manual.

- Building a Better Tomorrow Initiative (BBTI). An Atlantic Provincial Primary Health Care Initiative. (Health P.E.I. Copy, 2009): Team Building: Participants Manual.

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. (2010). A National Interprofessional Competency Framework. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Des_mznc7Rr8stsEhHxl8XMjgiYWzRIn/view

- Casimiro, L., Hall, P., Archibald, D., Kuziemsky, C., Brasset-Latulippe, A., & Varpio, L. (2011). Barriers and enablers to interprovider collaboration in health care: Research report. Beaulieu Consulting Inc

- Grant, R.W, Finnocchio,. L.J, and the California Primary Care Consortium Subcommittee on Interdisciplinary Collaboration. Interdisciplinary Collaborative Teams in Primary Care: A Model Curriculum and Resource Guide. San Francisco, CA: Pew Health Professions Commission, 1995.

- Hyer, K., Flaherty, E., Fairchild, S., Bottrell, M., Mezey, M., Fulmer, T., et al. (Eds.). (2003). Geriatric Interdisciplinary Team Training: The GITT Kit (2nd ed.). New York: John A. Hartford Foundation, Inc.

- John A. Hartford Foundation Inc. (2001). Geriatric Interdisciplinary Team training Program.

- Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (1994). The Wisdom of Teams. New York: HarperCollins. (p.45)

- Reeves, S., Goldman, J., Gilbert, J., Tepper, J., Silver, I., Suter, E., & Zwarenstein, M. (2011). A scoping review to improve conceptual clarity of interprovider interventions. Journal of Interprovider Care, 25, 167-174. doi:10.3109/13561820.2010.529960

- Tuckman, B.W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384-399.

- University of Manitoba. (Module 3 A; Facilitators Guide. Interprofessional Practice Education in Clinical Settings: Immersion Learning Activities. Appendix 1.

- University of Toronto. (2006). Educating health professionals for interprofessional care: becoming a leader in Interprofessional Education. Toronto: Author

Introduction

Conflict is a bi-product, a natural consequence, of people interacting with one another. It is natural; it is unavoidable and can have very positive consequences when handled properly.

Conflict is neither good nor bad, it is actually neutral. How we handle conflict will best determine whether it becomes a destructive or a constructive force in our relationships? If we handle it effectively, we may begin to see that conflict holds the potential for constructive outcomes.

This module and classroom session will provide you with information / tools to assist with conflict resolution.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation and thanks is extended to the following for permission to use content from their documentation to produce this education module on Interprofessional Conflict Resolution.

- Association of Ontario Health Centres. Building better team: A toolkit for strengthening team work in community health centres; Resources, tips and activities you can use to enhance collaboration.

- Baycrest: Baycrest Toolkit for interprofessional education and care.

- Building a Better Tomorrow Initiative (BBTI). An Atlantic Provincial Primary Health Care Initiative. (Health P.E.I. Copy, 2009): Conflict Resolution: Participants Manual.

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. A National Interprofessional Competency Framework (2010).

- Government of Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness (2009). Conflict Resolution: Participants Guide. Building a Better Tomorrow Together: Team Development for Primary Health Care Collaboration. Halifax NS: Author

- Government of Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness (2009). Conflict Resolution: Power Point Slide Presentation. Building a Better Tomorrow Together: Team Development for Primary Health Care Collaboration. Halifax NS: Author.

- University of Manitoba. (Module 3 A; Facilitators Guide. Interprofessional Practice Education in Clinical Settings: Immersion Learning Activities. Appendix 1.

- Winnipeg Regional Health Authority: Competency #6: Interprofessional Conflict Resolution.

Thank you is extended to Kelly Lackie (BScN MN PhD(c) RN; Faculty/Interprofessional Education

Lead, RN Professional Development Centre, Halifax, Nova Scotia) for reviewing the on line modules

In this module “Client ” means Patient / Resident/ Person

Learning Objectives

On completion of this module participants should have knowledge of the following:

- The definition of conflict.

- The conflict cycle.

- The competency statement from the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative on interprofessional conflict resolution.

- What interprofessional conflict resolution is.

- Potential sources of conflict in the interprofessional collaborative team.

- Approaches to resolve interprofessional conflict.

- What are your personal triggers.

What is Conflict?

According to the New Oxford American Dictionary conflict is:

A serious disagreement or argument; an incompatibility between two or more opinions, principles, or interests.