The Provincial Nursing Mentorship Program for New Graduate Nurses and Internationally Educated Nurses was made possible via funding in part from the Government of Canada's Foreign Qualification Recognition Program. The opinions and interpretations in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Appreciation and thanks is extended to the following for permission to use content from their documentation:

- Office of the Provincial Chief Nurse, Department of Health and Community Services, Newfoundland and Labrador, “Mentorship: Nurses Mentoring Nurses Module”, “Cultural Awareness and Responsiveness Module for Mentors for Internationally Educated Nurses (IENs)”.

- RN Professional Development Centre Halifax and the Nova Scotia Department of Health, “Nova Scotia Mentorship Program”.

- Canadian Nurses Association, “Achieving Excellence in Professional Practice, A Guide to Preceptorship and Mentorship”.

- University of Saskatchewan, “An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance”.

- Association of Nursing Directors & Supervisors of Ontario, Official Health Agencies and Public Health Education, Research and Development Ontario, “A Resource Guide for Implementing Nursing Mentorship in Public Health Units in Ontario”.

- Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions, “From Text Books to Texting - Addressing Issues of Intergenerational Diversity in the Nursing Workplace” and “Thriving in the Workplace - A Nurse’s Guide to Intergenerational Diversity”.

- Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region, “Mentoring Workshop Handbook for Protégés”.

Heather Rix, (Chair) RN BN

Nursing Policy Analyst/Advisor

Department of Health and Wellness

Vicki Foley, RN BN MN PhD

Assistant Professor

School of Nursing University of Prince Edward Island

Audrey Fraser, RN MN

Associate Director of Nursing Education

Queen Elizabeth Hospital

Cathy Sinclair, B.Sc. Health Education, B.Ed.

Health Recruiter

Department of Health and Wellness

Brenda Worth, RN BN MBA CHE

Director of Nursing

Prince County Hospital

Dorothy Dewar, RN, BScN CPN (C)

Nurse Research Lead

Health PEI

The mission of the Provincial Nursing Mentorship Program for New Graduate Nurses and Internationally Educated Nurses is to support the new graduate nurse and internationally educated nurse as they transition into the Prince Edward Island health care system.

For the purpose of the Provincial Nursing Mentorship Program for New Graduate Nurses and Internationally Educated Nurses, the designated individual(s) within the facility can be a nurse educator, manager, supervisor, clinical leader or senior nurse.

The Canadian Nurses Association (2004) defines mentorship as “a voluntary, mutually beneficial and long-term relationship where an experienced and knowledgeable leader (mentor) supports the maturation of a less-experienced nurse (mentee).” Mentorship programs are recognized as a tool to help new graduate nurses and internationally educated nurses (IEN) integrate into the work place. An IEN is a registered nurse or a licensed practical nurse who has graduated from a nursing school outside of Canada. The Provincial Nursing Mentorship Program for New Graduate Nurses and Internationally Educated Nurses will support the new graduate nurse and the internationally educated nurse as they navigate through the first year of practice with the purpose of retaining them in the nursing work force on Prince Edward Island. Mentorship is being listened to and listening to others, giving and receiving feedback, and increasing one’s skills and knowledge. The mentor is a resource to support the mentee as they transition into the work place. The Provincial Nursing Mentorship Program for New Graduate Nurses and Internationally Educated Nurses has been developed for RNs and LPNs practicing on Prince Edward Island.

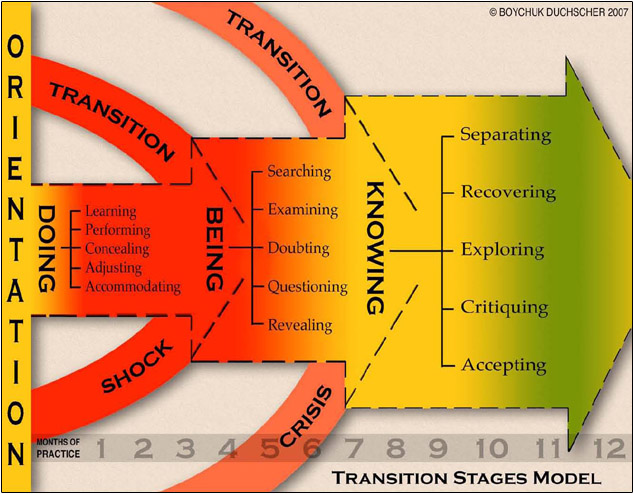

This program consists of independent sections - understanding the need for a mentorship program, getting started in the relationship, the resources required for the mentorship relationship and how to end the relationship after the year is completed. A theoretical framework, consisting of professional competencies, transition stages model, generational considerations for mentorship program, adult learning principles and setting smart goals, underpins the mentoring process. This framework assists in developing a mentoring practice beneficial to the mentor and mentee. The transition stages model developed by Dr Boychuk Duchscher is the main theory referred to in this program. Her current positions include Executive Director - Nursing The Future, Assistant Professor - Faculty of Nursing University of Calgary and Associate Member Representative for CNA 2011 – 2013. Duchscher’s doctoral research generated a model of the stages of transition that examine the multiple dimensions of moving from student to practitioner. Her research underscores the essential nature of mentoring relationships between seasoned and novice nurses. Knowing and understanding this theory will allow the mentor to support the mentee appropriately throughout their first year of practice.

Why develop a Mentorship Program for New Graduate Nurses and Internationally Educated Nurses?

Several studies have found that effective mentorship programs (i.e., new graduates matched with senior colleagues for psychological support, clinical instruction and supervision) enhance recruitment and retention of graduate nurses and facilitate the transition from student to professional nurse, (Boychuk Duchscher, 2009; DeSilva, 2009; Dyess, 2009; Ferguson, 2010; Fox, 2010).

After new employees finish orientation they wanted to have a “go to” person. They wanted someone more at an employee base level…., a peer to bounce ideas off of, a mentor they could go to with questions.3

Goals

- To guide mentors and mentees through a mentoring process with the expectation of ensuring a smooth transition for the mentee into nursing practice.

- To retain new graduate nurses and internationally educated nurses in the workforce.

- To provide a supportive environment for new graduate nurses and internationally educated nurses employed in Health PEI facilities.

- To assist new graduate nurses and internationally educated nurses in their transition to the complexities and nuances of nursing that they may not have been exposed to through their undergraduate curriculum or in their country of origin.13

Benefits of mentorship to mentor, mentee and institution

CNA considers mentoring an essential component within a quality professional practice environment (CNA, 2001). A range of benefits for the mentor, mentee and institutions have been identified as follows (Green & Puetzer, 2002; Kilcher & Skerries, 2003).

Mentor

- Enhances self – fulfilment

- Increased job satisfaction and feeling of value

- Increased learning, personal growth and leadership skills

- Motivation for new ideas

- Potential for career development

Mentee

- Increased competence

- Increased confidence and sense of security

- Decreased stress

- Increased job satisfaction

- Expanded networks

- Leadership development

- Insight in times of uncertainty

Institution

- Improved quality of care

- Increased ability to recruit

- Decreased attrition

- Increased commitment to the organization

- Development of partnerships and leaders

© Canadian Nurses Association. Reprinted with permission. Further reproduction prohibited.

Wondering about whether you could be a mentor?

Take the survey Nurturing the Mentor in You [PDF] (if not taken already). It is a tool to determine your readiness to be a mentor.

This survey is not a scientifically validated test; it is only for self-exploration purposes and to highlight some of the qualities of mentoring.

This section consists of tools for matching mentor and mentee, the ground rules for the mentoring relationship, a step by step guide for the mentoring relationship and the four categories of mentor competencies according the Canadian Nurses Association.

Tools for Matching Mentors and Mentees

Please complete The Mentor Scale [PDF] (if not completed already).

Complete and return the information to designated individual(s) within the facility.

Please note that these are just tools that may assist in the matching process. Their use does not guarantee a successful match.

To ensure minimal misunderstandings later, establish ground rules regarding your meetings – these may be agreed upon in writing. Insert ground rules in your mentor / mentee agreement when you first meet.

- Establish a regular time and place to meet.

- Meet once a month for the duration of the relationship.

- Meetings usually are one hour in length.

- Consider off unit, less distractions, more private.

- Consider any restraints to meet such as family needs, school, etc.

- Food: Can be comforting, provides a natural lead into discussion (coffee, snack).

- Interpersonal: establish boundaries, specific topics may be off limits, (personal information); this needs to be clearly defined at the beginning of the relationship.

- Allow for healthy ventilation of feelings.

- Clearly identify acceptable / unacceptable behaviours (e.g., complaining, whining). If negative behaviours occur, discuss with each other without repercussion. If behaviour continues, may require consultation with the designated individual(s) within the facility. The mentee should not overburden the mentor by demanding too much time and assistance or by becoming overly dependent on the mentor.

- Mentor and/or mentee may need to negotiate at the outset that either can end the relationship at any time with no hard feelings.

- Confidentiality: Essential for both parties (some exceptions apply) e.g., criminal behaviour will be reported to the appropriate agency and regulatory bodies.

- Record keeping: Keep documentation to a professional level and ensure it does not contain details of a personal nature.

- Keep record of learning plans, one copy for mentor, and one copy for mentee. Copies are to be available for viewing by the designated individual(s) within the facility.

- Complete paperwork at beginning of relationship and submit reports as outlined in step by step guide.

Voice mail, e-mail, texting, telephone, in-person meetings. Establish if mentor will accept phone calls at home after hours if mentee has questions.

Communication will be clear, frequent restating, summarizing for both parties. “Seek to understand then be understood” (Covey, 1989).

Review the Case Studies below regarding setting boundaries. Share feelings and validate feelings as well as facts.13

Establishing Boundaries

It is important to keep in mind the limits of the mentor role and recognize its boundaries. Negotiating these boundaries and clarifying them is an important facet of this phase of the mentoring relationship.

Case Study #1

Susan developed a learning plan in collaboration with her mentor Leila indicating that she wishes to become more active in nursing associations but problems at home, e.g., babysitting challenges, have become a barrier to goal attainment. Leila hopes to help Susan overcome her child care challenges so that she may attain her goals of increasing her participation in nursing association activities.

Leila reminds Susan of her accomplishments to date and congratulates her. She assists Susan in determining what is standing in her way of attaining her goal by:

- assisting Susan to identify and focus on barriers;

- acknowledging and supporting Susan’s perspective that these are barriers for her;

- helping Susan identifies options that may or may not address the barriers;

- encouraging Susan to evaluate the options in terms of feasibility, likelihood of success, most desirable;

- supporting and respecting Susan’s choice of solutions; and

- collaborating with Susan in adjusting her plan to incorporate the new solution and revising the

- goal of participating in professional associations accordingly.

After discussion with her mentor, Susan has decided to join one professional association rather than two to decrease the number of meetings she is required to attend, but has contacted the individual responsible for sending out the newsletter for the second association and will receive the newsletter even though she cannot attend the meetings at this time.13

Setting Boundaries:

Why it is important to set boundaries. Identifying when it may be appropriate to end a mentoring relationship.

Case Study #2:

Mary’s professional development goals centre on improving time management skills. Despite identifying her goal, her mentor, John, suspects that Mary’s behaviour such as coming late to work, missing team meetings, arguing loudly on the telephone with her boyfriend (she told co-workers he has abused her) is affecting her goal achievement. John realizes over the course of several mentorship meetings that Mary cannot focus on her professional life and blames her problems of “not fitting in” on the stress of being in an abusive relationship. John wishes to enter into a mentor/mentee relationship that assists Mary to cope with her personal situation.

While a mentorship relationship may involve an understanding of the mentee’s personal circumstances, the relevance of Mary’s personal situation to her professional goals is not substantiated in this situation. John assesses Mary’s problems as being related more to her personal life than her professional life and therefore would require a relationship outside the intent and involvement of a customary mentoring relationship. A learning contract developed at the beginning of the relationship demonstrated that goals and their milestones have been missed. John is relieved that he and Mary included statements around confidentiality in the contract, e.g., illegal behaviour will be reported to the appropriate agency and regulatory bodies.

John explains his reasoning to end the mentoring relationship to Mary and encourages her to identify and inform individuals or resources who may be a source of aid. John notifies the individual working with the program in his organization that the mentorship relationship is not working. John consults the Canadian Nurses Association Code of Ethics (2002) to decide what his ethical obligations are regarding follow-up individually, or in partnership, e.g., with Mary’s manager to resolve the problem. He ends the mentoring relationship and hopes that Mary will contact her identified sources of support.13

To access all documents mentioned in the Step by Step guide please double click links. Once accessed you will be able to print off these documents. Click back or return to return to program

Step by Step Guide to the Mentoring Relationship.

- Mentor and mentee are to complete The Mentor Scale. [PDF] This tool is provided to the designated individual(s) within the facility to assist with matching of mentor and mentee. No attempt to match will occur if two nurses choose each other to be mentor and mentee.

- Mentor and mentee agree to enter into a mentoring relationship.

- Review Provincial Nursing Mentorship Program for New Graduate Nurses and Internationally Educated Nurses. This is completed at a time when you can be released from your unit/work site. Complete Evaluation of Provincial Nursing Mentorship Program (mentor or mentee) on completion of program electronically.

- If mentoring an internationally educated nurse, please review the Cultural Awareness Module, and then complete Evaluation of Cultural Awareness Module and submit electronically.

- Complete the VARK questionnaire. Mentor and mentee require knowledge of how they learn in order to ensure that teaching and learning is relevant (e.g., kinesthetic learner learns by doing).

- Mentee will need to print:

Learning Plan [PDF]

Mentor / Mentee Agreement [PDF]

Mentoring Session Record [PDF]Please open these links now and print a copy of each. Take to the first mentorship meeting.

- The mentee should access the New Graduate / IEN Self-Empowerment Checklist [PDF] (print and complete prior to first mentorship meeting) to determine what may be most beneficial to their development. Through reflection on this list, goals for the mentoring relationship and content of the learning plan may be developed. The mentee should have proposals for content of the learning plan prepared to discuss with their mentor at the first meeting.

- Initial Meeting: Developing a Learning Plan

- Mentor and mentee are released from their respective unit(s).

- Mentor and mentee discuss and establish ground rules for relationship. Review this section of Provincial Nursing Mentorship Program for New Graduate Nurses and Internationally Educated Nurses, if needed.

- Mentor and mentee sign a mentor and mentee agreement form and return a copy to designated individual(s) within the facility. This formalizes the mentorship process. It places no obligation on mentor or mentee except those agreed to by both parties. The relationship and roles must be formed with a clear understanding of expectations and responsibilities.

- Mentor and mentee decide on goals for mentee and record goals on learning plan. There is a sample Learning Plan, [PDF] and questions that can help develop a Learning Plan [PDF] (Appendix B) to assist with this process. (Review prior to first meeting if required). Click on each document to access.

Subsequent Meetings:

- At the beginning of each meeting mentor and mentee will evaluate the learning plan and acknowledge the achievement of goals.

- Look at remaining goals and review target dates. Assess how realistic it is to achieve these goals and maintain target date of completion. If unrealistic re evaluate and select a new target date. Document progress.

- Ensure completion of appropriate documentation at each meeting (Appendix B - Mentoring Session Record). This is supplied to maintain focus while meeting. (Mentor to print off and bring to meetings)

- Please ensure you keep a copy of all documents for your records.

Closure and Separation:

- Formal relationship ends approximately 12 months from start date.

- Complete Mentorship Program Progress Report at 3 months, 6 months and at the last meeting between mentor and mentee give the report to designated individual(s) within the facility. (Progress Report can be found in the Documents section on the home page)

- Complete Evaluation on Completion of Mentoring Relationship and submit electronically.

Competencies are the knowledge, skills, judgment and personal attributes required for a person to practice safely and ethically in a designated role and setting (CNA, 2002, p.15).

CNA 2004 (p.40) divides mentor competencies into 4 main categories:

1. Personal Attributes

- Demonstrates effective communication skills.

- Displays respect, patience and good listening skills.

- Demonstrates trustworthiness in working relationships.

- Demonstrates a positive attitude, enthusiasm, optimism and energy about the work environment, nursing and mentoring.

- Expresses belief in the value and potential of others.

- Is open and accepting of the diversity of others.

- Demonstrates confidence.

2. Modelling Excellence in Professional Practice

- Displays commitment to nurses and to the nursing profession.

- Displays commitment to the goals of the organization or the team.

- Demonstrates strong knowledge, judgment, skill and caring in their domain of practice.

- Is credible and respected by colleagues, the organization and the community.

- Demonstrates critical thinking by challenging ideas, knowledge and practice, as appropriate.

- Actively expands knowledge base using research evidence and remains current with latest thinking and best practices in area of expertise.

- Uses an ethical framework to guide professional practice and interpersonal relationships.

- Uses socio-political knowledge of the organization to work effectively within or beyond the system.

- Conveys ability to see the "big picture" (historical, political or systems context).

- Uses a strong and diverse network to collaborate with others in the work setting and the broader. system (i.e., health care system and wider community, where relevant).

- Demonstrates effective negotiation and conflict-resolution skills.

3. Fostering an Effective Mentor/Mentee Relationship

- Establishes trust and maintains confidentiality.

- Makes time for the mentoring relationship and is approachable and welcoming.

- Demonstrates respect for the mentee as an individual and belief in the mentee's potential.

- Demonstrates caring for the well-being of the mentee.

- Nurtures the mentee by providing support, encouragement and a safe relationship.

- Provides honest feedback and gentle confrontation; becomes a "critical friend".

- Engages mutually in the mentoring relationship (i.e., is willing to share of self and is open to personal change).

- Reflects on own interactions to challenge, stimulate and support the mentee.

- Collaborates and negotiates in setting the purpose, goals, process, boundaries and evaluation of the mentoring relationship.

- Plans for appropriate closure or transition of the relationship.

- Celebrates achievements and successes with the mentee.

- Respects mentee's right to make decisions, but recognizes when it is ethically necessary to intervene to prevent harm.

- Demonstrates an understanding and respect for the power differential between the mentor and mentee.

4. Fostering Growth

- Coaches the mentee towards goal achievement

- Encourages the mentee to identify own strengths, gaps and growth potential

- Supports the mentee in the selection of appropriate and realistic goals

- Guides the mentee to identify options/activities to meet goals

- Encourages the mentee to identify realistic timelines for goal achievement reflecting work and life balance

- Guides the mentee to select an optimum level of challenge within their role, setting or domain of practice (e.g., range of goals, incremental levels of difficulty or complexity)

- Guides the mentee to identify, clarify, define and manage barriers, problems and issues

- Facilitates the mentee's access to a wide variety of resources and opportunities to meet goals (e.g., journals, space, activities, people, literature, agencies, interest groups, committees, funding)

- Encourages independence and autonomy

- Encourages the mentee to reflect on own growth or achievements and future actions

- Questions, probes and guides the mentee to explore new perspectives and insights

- Knows when to provide direction and when to challenge the mentee

- Encourages learning from mistakes and/or disappointments

- Guides the mentee to avoid pitfalls and manage crises

- Guides the mentee to develop own leadership in practice

- Chooses an appropriate balance when contributing own experiences (i.e., good story-telling and metaphors), as relevant

- Guides the mentee to develop effective negotiation and conflict-resolution skill

- Encourages the mentee in a process of visioning through free thinking, creativity and innovation, as relevant to the setting

- Challenges the mentee by offering new ideas, knowledge and practices

- Assists the mentee to enhance the quality of the professional practice environment and to initiate change, where relevant and possible

- Assists mentee to identify an alternate view of the future that may not be seen by mentee (i.e., looking at the "big picture", seeing beyond the details)

- Assists the mentee to identify patterns, themes and trends and to acquire new perspectives

- Encourages and supports the mentee in risk taking (i.e., in developing new knowledge, skills and innovations for the workplace

- Facilitates the mentee's integration within the organization and larger professional community, as relevant to the setting

- Shares professional networks with mentee

- Helps the mentee navigate the system

- Shares informal rules

- Promotes the mentee by communicating their successes within the organization and the profession

- Shares ideas about opportunities for advancement

- Encourages the mentee to engage in professional leadership activities such as presentations, partnerships, specialty associations

- Acts as a champion for the mentee

- Solicits corporate (i.e., organizational) support for the mentee

After reviewing the competencies developed by CNA, reflect on the below questions. This reflection is for your benefit. Suggested responses are provided for information only.

1) What personal attributes should a mentor display when a mentee is seeking help to make an important decision?

Suggested answer:

Mentor should display respect, patience and good listening skills; ask questions; provide constructive feedback; help mentee consider different options; provide guidance.

2) What characteristics do you feel are most important to foster an effective mentoring relationship?

Suggested answer:

Establish trust by showing respect for the mentee; maintain confidentiality; mentor is welcoming and approachable; demonstrate care for the mentee's well-being; respect mentee's right to make decisions but recognize when it is ethically necessary to intervene to prevent harm; celebrate achievements and successes with the mentee.

3) What do you feel is the best way to model excellence in professional practice?

Suggested answer:

Show commitment to nurses and the nursing practice; use critical thinking by challenging ideas, knowledge and practice, as appropriate; is credible and respected by colleagues, the organization and community; able to teach; provide leadership; guide the mentee; help to develop confidence; aware of the stresses nurses face; aware of organizational culture.

4) What is the best way to coach the mentee towards achieving their goal?

Suggested answer:

Encourage the mentee to identify their own strengths, gaps, and growth potential; guide mentee to identify options and activities to meet goals; facilitate the mentee's access to a wide variety of resources and opportunities to meet their goals; encourage independence and autonomy.10

©Canadian Nurses Association. Reprinted with permission. Further reproduction prohibited.

Transition Stages Model

This model will provide both the mentor and mentee with knowledge of the stages of transition experienced by the mentee during their first year of practice as they integrate into the workplace. The mentor plays an important role in supporting the mentee through the process.

| Stage 1: Doing | Stage 2: Being | Stage 3: Knowing |

|---|---|---|

| The Graduate is | ||

| Performing | Examining | Recovering |

| Concealing | Doubting | Exploring |

| Adjusting | Questioning | Critiquing |

| Accommodating | Revealing | Accepting |

New graduate nurses entering the work place transition through different phases as they negotiate their way in the practice environment during their first year post graduation. These phases begin with a reality check when they discover differences between the educational and practicing environment. Boychuk Duchscher identifies three distinctly different stages in the transition process of new graduates into the work place. The stages occur from 1 -3 months (doing), 3 – 6 months (being), and 6 – 12 months (knowing). Knowing and understanding this theory will allow the mentor to identify where their mentee is in the transition and to support them appropriately on their journey.

| Stage 1: Doing | Stage 2: Being | Stage 3: Knowing |

|

|

|

According to Boychuk Duchscher (2008), issues commonly cited as troublesome for newly graduated nurses during the initial 12 months:

- Issues with relationships with colleagues

- Work load demands

- Organization and prioritizing work load

- Decision making

- Direct care Judgments

- Communication with physicians

(Boychuk Duchscher, 2008, p. 443)

For more information on this theory please refer to Boychuk Duchscher, J. (2006) From Surviving to Thriving: Navigating the First Year of Professional Practice. Saskatchewan. Saskatoon Fastprint.

Stage 1 - Doing

Learning

- New graduates at this stage will be most comfortable in the learning role and least comfortable applying that knowledge. They feel insecure about what they know because the situations ‘look’ different than they did when they were students. ‘Real’ patients have many more variables than they can be theoretically prepared for.

- They are more comfortable with theory. They will often ‘default’ to this when stressed because it is safe and familiar.

- There is much to be ‘learned’ in their new professional environment. For example, who’s who, the institutional policies and regulations, their professional responsibilities, how to manage their workload, who they can trust, what skills they are required to do, or who they can turn to.

- Remember that the new graduate is a typical ‘adult learner’ in that they do best when they have a chance to apply what they have learned shortly after being introduced to the skill or theory.

Support:

What can you do to facilitate the new graduate’s learning and make them more comfortable with what they know?

Is there a way for you to encourage them to ‘learn’ and ‘perform’ – giving them time to repeatedly practice and gain a familiarity with what is expected of them (roles, responsibilities, nursing tasks, etc.)?

Performing

- New graduates at this stage will be most concerned with their ability to ‘perform’ the tasks and skills that are required of them.

- They are aware that they are being ‘watched’ and ‘judged’ in accordance with how well they perform. Acceptance of themselves is often dependent upon the mentor’s acceptance of them. They will take their cues about their practice from those around them.

- The growing professional self-concept of the new graduate depends on a healthy facilitation of their new roles and responsibilities. Very often, they have never performed those roles nor been given complete responsibility for patients (this is virtually impossible when you are a ‘student’). The feeling of being held not only responsible for decision made regarding your patients, but accountable for those decisions can be initially frightening and overwhelming.

- Graduates who are permitted and encouraged to ‘practice’ their skills and thinking under you watchful eye will do better overall.

Support:

What can you do as a nursing team/institutional culture to facilitate the growing skill level of the new graduate?

Concealing

- New graduates at this stage are insecure about who they are and what they know or are capable of doing.

- Depending on the age, maturity level (their life experience) and degree of self-confidence of the graduate, there may be an attempt to conceal their feelings of inadequacy or incompetence from you. You must understand that to reveal these means taking the risk that they will not be respected or accepted by the very colleagues they admire and seek to ‘be like’. This has significant implications for their evolving sense of themselves as professional nurses.

- Encouraging and understanding conversation will do much to ‘bring out’ these feeling of the graduate. If the seasoned nurse can share what it felt like when THEY were a new graduate, or let the novice know that their seasoned colleague is not always ‘perfect’ (they perceive seasoned nurse as such initially) will let them know the graduate has something of value to offer even though they are new.

Support:

What can you as a new graduate support do to make the graduate more comfortable around you?

How can you encourage them to feel safe sharing how they are feeling about the changes they are experiencing?

Adjusting

- New graduates at this stage are adjusting to many new roles, relationships and levels of responsibility. It was one thing to care for patients as a student when they knew that there was a faculty person to check in with, and when they knew that the ultimate responsibility of that patient lay with the Registered Nurse caring for them. Now the buck stops with them and the thought that ‘I have to know everything now’ is overwhelming (not to mention unrealistic)!

- Many graduates are adjusting equally to changes in their personal lives as they are to changes in their professional lives. Many are moving residences, changing relationships with friends and partners, managing and taking responsibility for their lives (and their finances!) for the first time, trying to understand ‘ what a nurse actually is’ and how they fit into that idea, and trying to find out who they are again now that they have time to ‘play’. All of this is happening at the same time.

- Because there is a significant amount of energy being consumed by a variety of personal as well as professional adjustment in the initial 6 months of employment, new graduates should be actively discouraged from working overtime – ‘down’ time is critical during this rapid growth phase.

Support:

What change is your new graduate making in their lives (i.e., Are they changing relationships, managing their finances for the first time – buying their first home)?

How are those changes affecting their ability to focus, commit, and engage in their new role?

What kinds of discrepancies do they see between what nursing IS and what they thought it would be?

How can you assist them to bridge those differences?

What plans are you as a team going to make to assist the new graduate to adjust to their new role?

Accommodating

- New graduates at this stage often find themselves caught between a rock and a hard place. They have never experienced many of things they are seeing and doing before. For example, they may find themselves unfamiliar with a particular unit routine, a technique for cleansing a wound, or a particular attitude toward patients or colleagues that conflict with their own way of relating to others. It is their development task at this stage to figure out what it is they simply need to ‘accept’ and what they can (and should) ‘modify’ according to their own way of doing things (perhaps a new theory that they were taught) or their own standards of practice.

- They are seeking your counsel and your modelling for how to ‘be’ in this new world. They require rationale for why things are the way they are so that they are better equipped to decide if that is something they should ‘accommodate’ in their thinking or if it is something that runs contrary to their thinking. These are tough decisions, particularly when you want to be accepted by those individuals with whose practice you might take issue. Figuring out ‘who you are’ at a time when you also need to ‘belong’ is one of the greatest professional adjustment we will make.

Support:

What can you do to help the new grad balance what ‘should be’ with what ‘is’ in the ‘real’ world?

What can you do to encourage them to develop their own way of practicing as a nurse?

Stage 2 - Being

Searching

- Ever heard the phrase ‘young enough to do it, but old enough to know better’? Well, the new graduates at this stage have some knowledge under their belt and are likely exercising it. They have been ‘around’ for a while now (albeit a short period of time in the grand scheme of things and when compared to their seasoned colleagues) and they are getting to know what is expected of them and they are making sense of what a ‘nurse’ does and is – some of what they find may satisfy them, but some aspects of their roles as nurses in the real world might not be what they wanted or thought they would be.

- They will begin a search for meaning in what they are doing at this point – they are trying to understand why things are the way they are. They may no longer be satisfied with just ‘doing’ what they are told without rationale, or just complying with the ‘way things are’ because ‘that’s the way we do things around here’. This is an important stage in their development as nurses in their own right and they may begin to look around them, searching for explanations that can answer that million dollar question, WHY??? This is NOT a challenge of the seasoned nurse him or herself, but it may challenge that nurse to examine the reasoning behind their practice.

Support:

What can you do as a team to facilitate your new graduate’s need to understand the rationale for what they are doing?

How can both you and the new graduate search for meaning together in what you do as nurses?

Examining

- New graduates at this stage are even more aware that there are differences in what they are actually doing and what they were educated or prepared to do. Because they are not as stressed about ‘doing’, they can lift their gaze from the tasks and routines and begin to examine things for what they are.

- The growing identity of the new nurse may well depend on their availability to engage in this examination. What they need in doing this is to be guided by a mentor who understands that real practice is NEVER ideal, but that there are ‘lines’ that we must decide NOT to cross when things get hairy. The new graduate needs to understand where those lines are and how to negotiate the mine-field that comprises the daily issues and clinical situations about which we make nursing judgments and decisions that result in actions with life altering consequences for those under our care.

Support:

What can you do as a nursing team to examine what you are doing and why you are doing it?

How can you fit this into your busy working ‘schedule’?

Doubting

New graduates may be in doubt of many things at this stage:

- They may wonder why they went into nursing at all (mostly because they may still not be sure what they offer to the profession);

- They may question whether or not they are capable of reaching the level of expertise they see in their seasoned colleagues or mentor;

- They may doubt that they will ever experience the professional respect as nurses that they feel they should be afforded (this will be particularly evident in institutions or unit cultures that are hierarchical,where nurses of varying responsibility levels do not act in a collegial fashion, where nurses and physicians do not engage in a collaborative professional compliment, or where nurses are not valued for their knowledge, skill, clinical judgment and decision making);

- They may doubt that their lives will ever be balanced (they will likely be exceptionally tired at this stage and this exhaustion is feeding their doubt) or that they will achieve the balance their seasoned counterparts seem to have.

The doubts are about who they are as professional and as maturing men/women in a world that is ‘new’ to them. New graduates actually experience grief during this stage – while they are gaining so much as they grow, they are also letting go of ways of being and thinking that have framed their lives until now.

Support:

What can you as a seasoned supporter do to enhance the graduate’s evolving professional self-esteem?

How can the nursing team ensure that the new graduates’ doubts are acknowledged and reflected upon?

How can you reassure that graduate that much of what they are feeling are ‘growing pains’ and that time and experience will see them through?

How can you support them through this struggle?

Questioning

- The new graduate’s thinking is rapidly advancing as they become comfortable with the routines and tasks. They may begin to look around them and begin to question why things are the way they are.

- Some of the questioning may be coming from a sense of frustration and their own lack of knowledge and understanding about the underlying rationale for existing ways of being.

- They may be questioning the role of nurses in the healthcare system or they may be questioning the functioning of certain aspects of the unit, institution/health centre, or healthcare system itself. All of the questions are important. This stage is about adjusting to and making sense of the environment in which they have chosen to commit their life’s work. The fit between ‘who they are’ and ‘where they work’ is important to their evolving image of their work. They may be struggling with aspects of either themselves or the system that they see as the origins of a ‘misfit’ and a need to be able to work through their thoughts and feelings about the incongruencies. Questioning is a way to get the information they need to make sense of their world.

Support:

How can these questions be brought to the surface so that you can engage in discussion about them?

What strategies can be used to encourage the new graduate to reflect on the in congruencies between themselves and where they are working so that they can make sense of both the origins of their struggles and possible solutions?

Where do the experiences of the seasoned practitioner, manager and educator fit into this process?

Revealing

- Because the new graduate has more time and energy (the time and energy that was going into learning the routines, performing their roles competently, and understanding how to relate to others with whom they work has been greatly reduced as the familiarity with those aspects of their work has increased), they ‘see’ more of the differences between what they expected and what they are finding in the ‘real’ world.

- So much of what they didn’t know (or couldn’t be exposed to) as a student is being ‘revealed’ to them now. Sometimes the way we see thing (and people!) is more glorified than perhaps it (or they) really are. This is what ‘reality’ is all about and there are elements of reality that simply need to be accepted once revealed. This is a critical time for the new graduate and it is a critical time in your relationship – YOU are the expert to whom they are going to look for guidance on how you balanced ‘reality’ with your dreams and aspirations. How does one maintain that very tenuous balance between striving for what can be while working within what is?

Support:

What can you do as a mentoring team to help each other understand what nursing is, what it could be, where nursing is, and how you can get it to where you want it to be? With whom might you partner on your unit or in your institution to help you reach the goals you have for your career and profession?

Stage 3 - Knowing

Separating

- New graduates at this stage may need some space. The exhaustion of simply ‘surviving’ the first stage of their professional role transition ‘without killing anyone’, followed by the intensity of emotions and the energy consumed by adjusting to the differences in their lives that characterize the second stage may cause them to withdraw from you and from their surroundings during the third stage – they may need to separate to get some perspective.

- Because they are trying to distinguish ‘me’ from ‘they’ at this stage of their development, the new graduate may need to ‘try on’ a more advanced and independent level of practice. This means they may be looking for a ‘different’ relationship with their mentor and the colleagues around them. They may want more ‘give and take’ in the relationship and they may put distance between themselves and their mentor. This is natural and how the mentor responds may dictate the future directions of the partnership.

Reflections for Supporters:

What can you do as a team to foster interdependence (versus dependence) of the new graduate with those around them?

How does the mentoring relationship need to change over time to accommodate both the learning needs and the evolving independent practice of the new nurse?

What challenges or strains can surface in the relationship at this time and how might you address them?

Recovering

- WHEW!!!!! What the heck happened there??

- The new graduate might be wondering what on earth happened to them over the past 8 months and likely needs some time to ‘recover’ from the draining experience of making their initial transition to professional practice.

- This process is related to the ‘separating’ process in that the separation is protective for the graduate – they may want to spend more time with family and friends (in part because they may feel as though they have neglected them these past months as they have been absorbed in making the transition) with whom they feel connected. They may well want to engage in personal activities (i.e., hobbies they want to reactivate) or just spend time away from the work environment. It is very important that new graduates be encouraged to pursue activities OUTSIDE of nursing (not spending all their unscheduled work time ‘working’) that can give them a balanced sense of development, success and fulfilment.

- Graduates may well be making decision at this point about the meaning of their experience. Depending on the degree of adjustment for the graduate (this is VERY individual), the recovery time will vary in intensity and duration.

Reflections for Supporters:

What can mentors do to encourage a balance in the life of the mentee?

What insights about balancing personal and professional life can the mentor offer the new graduate?

What process will you use as a team to assist the new graduate to reflect on what happened to them and how it is influencing their thoughts and feeling about nursing and their career?

Exploring

- As the new graduate recovers their energy, they will begin to think about their future. Exploring one’s nursing career trajectory is important, particularly for the newest generation of nurses who have grown up in a culture that is constantly ‘moving’. While we all ‘live’ in, and have learned to adjust to our contemporary society, this newest cohort grew up in a culture that values temporariness, mobility, flexibility and knowledge/skill as the ‘currency’ of success. Without always understanding why, these young individuals need to be ‘on the move’. This may be about advancing their skills, knowledge, thinking, or may be about moving their actions forward or it may mean literally changing roles, units, institutions or even geographical locations.

- This stage is likely a good time for the mentoring team to think about the career path and plan of the new graduate.

Some questions to ask the graduate when assisting them through this process:

- What kind of nurse do you want to be (attributes or professional characteristics)?

- What areas of practice are you most interested in pursuing in the next year?

- What do you see yourself doing as a nurse in 5 years? What do you need to do (ongoing education, skill acquisition, practice experience and knowledge) to get where you want to be? Who can help you get there?}

- What does the career plan look like (what, how, when, who, where) for this new graduate?

Critiquing

- In order to explore, understand, and then reconstruct their vision of what nursing is and how that fits with who they are requires a certain level of critique.

- Critique does not necessarily equate with ‘criticism”. Just because a graduate critiques individuals and situations with whom they interact does not mean they are criticizing the people or even the structures (units or institutions) within which they function. What they are doing (and NEED to do) is deconstructing what exists in their world for the purpose of reconstructing it so that it is a better match with their aspirations and expectations.

Reflections for Supporters:

What role does the mentor play in facilitating an honest and open critique of the professional landscape?

How might the grounded perspective of the seasoned nurse assist the new graduate to make sense of the ‘pieces’ of the puzzle generated by this deconstruction of what they see, think and feel about the nursing profession and their work?

Accepting

- This process is about distinguishing those elements of the process of critique that the graduate can ‘accept’ and those they are unable to accept as they are. This many mean that the graduate has to reconfigure their expectations about something (i.e., in order to accomplish their workload, they need to find a way to assess the patient and teach them at the same time) or it may mean that they need to initiate a change (i.e., approach the manager about staffing issues, request shift changes or targeted clinical experiences, or address a specific issue/conflict in the work environment). Learning how the mentor coped with their own adjustments and integrated their nursing standards into their nursing workload may assist the graduate in generating their own strategies.

- It must be acknowledge that untenable conflicts may occur for the graduate as they work their way through this process of accepting (or NOT accepting) what they find in the ‘real’ world. It is important to ensure that both the mentor and the mentee do not perceive any practice or work incompatibilities for the graduate as a statement of failure on the part of either the new graduate or the mentor. The responsibility of the mentoring team is to recognize that an incompatibility exists, take steps to resolve it (i.e., meet with the manager or educator to strategize on resolution), and then be able and willing to plan for change if the situation remains unresolved.

Reflections for Supporters:

What process can the mentoring team use to bring to the surface the issues that remain a conflict for the new graduate?

How will your dialogue change during this final stage?

What questions would be appropriate for the mentor to ask to assist the graduate to explore the challenges and triumphs of their transition and the meaning of these for their future?

© RN Professional Development Centre and Nova Scotia Department of Health, Halifax, N.S. 2011

Learning underlies the process, purpose and outcome of mentoring. The mentoring practice takes the approach that a mentee is responsible for learning and a mentor facilitates this learning. This view is consistent with the principles of self-directed learning as articulated by Knowles (1980). The key principles of adult learning include:

- Adults learn best when they are involved in diagnosing, planning, implementing, and evaluating their own learning.

- The role of the facilitator is to create and maintain a supportive climate Adult Learning Principles and Mentoring Practices that promotes conditions necessary for learning to take place.

- Adult learners have a need to be self-directing.

- Readiness for learning increases when there is a specific need to know.

- Life's experiences are a primary learning resource; the life experiences of others add enrichment to the learning process.

- Adult learners have an inherent need for immediacy of application.

- Adults respond best to learning when they are internally motivated to learn.12

The below Adult Learning Principles and Mentoring Practices Chart12 demonstrates the relationship between adult learning principles and the mentoring practice.

For each adult learning principle, the tasks to be performed by the mentor and mentee in a mentoring relationship is aligned.

Adult Learning Principles and Mentoring Practices

| Adult Learning Principles | Mentor | Mentee |

|---|---|---|

| Adults learn best when they are involved in diagnosing, planning, implementing, and evaluating their own learning. | Facilitates learning activities and encourages the mentee to share, question, and practice knowledge and skills. | Actively plans and carries out learning activities. |

| The role of the facilitator is to create and maintain a supportive climate that promotes conditions necessary for learning to take place. | Creates a climate of respect and a physical and social climate conducive to learning. Acknowledges the experiences each bring to the learning environment. |

Acts in partnership to share ideas, content and experience. |

| Adult learners have a need to be self-directing. | Assists mentee in determining learning needs and to incorporate these into a learning contract or learning plan. Uses these resources to guide discussion and agree to mentee's goals and objectives. |

Determines own learning needs and discusses how best to incorporate these into a learning contract or learning plan. |

| Readiness for learning increases when there is a specific need to know. | Works with the mentee to clearly state the learning goals at the beginning of the activity. | Commits to the learning goals and understands how the learning event will help achieve them. |

| Life's experiences are a primary learning resource; the life experiences of others add enrichment to the learning process. | Relates new material to the mentee's existing knowledge and experience. Guides learning by helping the mentee connect their life experiences and prior learning to the new information. |

Brings valuable personal and professional experience to the relationship. Relates experiences to the new learning event. |

| Adult learners have an inherent need for immediacy of application. | Ensures learning is applicable to the mentee's work or other responsibilities of value. | Learns effectively when there is a specific, work-related problem to be solved. |

| Adults respond best to learning when they are internally motivated to learn. | Recognizes different learning styles (influenced by personality, intelligence, experiences, education, culture). Adjusts learning strategies to accommodate mentee's learning style. |

Aware of own learning style and is willing to adopt and change learning style to accomplish learning goals. |

Based on these principles of adult learning, three assumptions can be made about the nature of mentoring:

- Mentoring can be a powerful growth experience for both the mentor and the mentee.

- Mentoring is a process of engagement that is most successful when done collaboratively.

- Mentoring is a reflective process that requires preparation and dedication.15

Nursing comprises of four distinct generations in the work force currently. This program provides information about the four generations. It provides an overview of what each generation is good at and what challenges exist when different generations work together.

The current nursing workforce consists of four demographic groups: Veterans, Baby Boomers, Generation X and Generation Y. Each generation shares commonalities because of the time line in which they were born. It is important to remember that people are individuals and while they share some common beliefs with their own generation they do not share all points in this theory.

- The Veterans, a.k.a. Traditionalists, a.k.a. Silent Generation (born between 1925 and 1944)

- The Baby Boomers, a.k.a. Sandwich Generation (born between 1945 and 1964)

- Generation X, a.k.a. Nexers (born between 1965 and 1980)

- Generation Y, a.k.a. Millennials (born between 1981 and 2000)

Veterans/Traditionalists, Born between 1925-1945

Nurses from the Traditionalist or Veteran generation entered the workplace when the future was predictable. These nurses tend to be respectful of authority and disciplined in their work habits. They are averse to risk. They are less likely to question organizational practices. They are more likely to seek employment in structured settings.

Baby Boomers, Born between 1946-1964

Nurses from this group have traditional work values and ethics similar to the Veterans, but they are more materialistic. They are prepared to work long hours in return for rewards. The Baby Boomers define themselves through their jobs and work performance. Many nurses have worked for the same institution for many years.

Gen X/Nexus Generation, Born between 1965-1980

Many nurses from this generation entered the labour market at a time of significant hospital restructuring and large-scale layoffs of nurses. Many of these nurses were unable to find fulltime employment. They were forced to Generational Table take several part-time positions or leave Canada in order to pursue a career in nursing.

Gen Y/Millennials, Born between 1981-2000

These nurses are members of the first cohort of truly global citizens. They are self confident, highly educated and technologically savvy. They value greater work flexibility and are likely to change careers or professions five to eight times in their lifetime. They value collective action over competition. They assume technology will be assimilated into work practices. They tend to select positions based on the composition of the work unit. They expect a collaborative team approach with constant positive reinforcement.18

The below Generational Table demonstrates a brief overview of what each generation is good at, what we should celebrate about each generation and what challenges exist while working with different generations.10

| Veterans | Baby Boomers | Generation X | Generation Y |

|---|---|---|---|

| What they are good at | |||

| Following rules and meeting deadlines | Story telling | Being resourceful | Prioritizing work life balance |

| Knowing policy and procedures | Value and follow policies and procedures | Technology | Using technology for instant access to current and accurate information |

| Being conscious of resources | Protesting and marching for causes | Setting goals and meeting them | Little fear of authority |

| Valuing tradition | Bringing experience to the table | Being leaders | Great team players |

| Identifying with their jobs and valuing loyalty | Projects | Going green, preserving the environment | |

| Critical and independent thought and confidence | Knowledgeable of global issues, awareness of being a global citizen | ||

| Maintaining enthusiasm in the workplace | |||

| Possess a can-do attitude and self confidence | |||

| What we should celebrate about each generation | |||

| Hard workers | Fun people | Love a challenge, get things done | Fun |

| Loyalty to organization | Invaluable experience and stories to tell | Work is a means to achieving a goal | Care about the environment |

| Work well with Generation X | Produced Generation X and Y | Technologically savvy | Good team players |

| Possess a healthy skepticism | Show initiative when others may sit back | Excellent critical thinking skills and challenge conventional thought | |

| Great advocates for organizational change that enhances work-life balance | Hard workers if they like their job and co-workers treat them kindly | ||

| Next generation of leaders | |||

| Human beings worthy of being treated with dignity and respect | Human beings worthy of being treated with dignity and respect | Human beings worthy of being treated with dignity and respect | Human beings worthy of being treated with dignity and respect |

| What may be challenging | |||

| Do not say much | View younger generations as having less loyalty, less preparation for clinical practice | Will leave workplace if goals not met | Want to do things the way they learned how |

| Work load challenges due to their own age | Resistant to change | Very independent and self directing | Do not respond well to control and command leadership styles |

| Think black and white, no grey | Been there, done that, attitude | May threaten to leave if they do not get what they want | Need their boss to be their friend |

| Talk about the way things used to be | Want work-life balance, but do not know how to practice it | May not need as much guidance as others may think they do | Rely on the Internet and text communication for information |

| Tend to love patients, hate paperwork | Their expression of confidence | Inclined not to read bulletin board or practice manuals | |

| Reluctance to sacrifice personal time for sake of work | |||

| What they need | |||

| Clarity on underlying rationale processes and decisions related to actions | Leave them alone, as have been downsized, bent, folded, twisted by rapid health care change | Authentic leadership and honesty | To be mentored |

| Opportunities to be heard and to feel valued | Clarity, honesty and sincerity | Adequate compensation / benefits | To be challenged |

| Recognized for the important mentorship they provide the younger generations | Flexible work hours | Honesty | |

| Fair pay, appropriate benefits, ultimately their pension | Tangible recognition for accomplishments | To have fun at work | |

| Work for trustworthy organizations | Work-life balance | ||

| Need to be able to ask any questions around technology without being demeaned | Healthy workplace relationships | ||

| Flexibility to manage demands of personal lives | Regular feedback | ||

| To feel valued and treated with dignity and respect | To feel valued and treated with dignity and respect | To feel valued and treated with dignity and respect |

This will help the mentor and mentee set goals for duration of the mentoring relationship.

Utilizing SMART Goals may assist you develop attainable goals during the mentoring process.

SMART is an acronym that is used as a foundation for setting goals:

S – Specific, significant, stretching

M – Measurable, meaningful, motivational

A – Agreed upon, attainable, achievable, acceptable, action-oriented

R – Realistic, relevant, reasonable, rewarding, results-oriented

T – Time-based, timely, tangible, trackable

Specific:

- Specific and significant

- Well defined

- Clear to anyone that has a basic knowledge of the situation

A specific goal has a much greater chance of being accomplished than a general goal. To set a specific goal you must answer the six ‘W’ questions:

Who: Who is involved?

What: What do I want to accomplish?

Where: Identify a location.

When: Establish a time frame.

Which: Identify requirements and constraints

Why: Specific reasons, purpose or benefits of accomplishing the goal.

Example:

A general goal would be “Learn how to access a PICC line” but a specific goal would say, “Patient X has a PICC line, with my mentors help I will learn how to access this line following hospital policy and procedure”.

Measurable:

- Meaning and motivational

- Know if the goal is obtainable and how far away completion is

- Know when it has been achieved

Establish concrete criteria for measuring progress toward the attainment of each goal you set. When you measure your progress, you stay on track, reach your target dates, and feel positive about what you have achieved.

To determine if your goal is measurable; ask questions such as, How much? How many? How will I know when it is accomplished?

Agreed Upon:

- Attainable, achievable, acceptable and action-oriented

- Agreement between the mentor and the mentee of what the goals should be

When you identify goals that are most important to you, you begin to figure out ways you can make them come true. You develop the attitudes, abilities, and skills to reach them. You begin seeing previously overlooked opportunities to bring yourself closer to the achievement of our goals.

You can attain goals you set when you plan how you will achieve them and establish a time frame that allows you to carry out those steps. Goals that may have seemed far away and out of reach eventually move closer and become attainable.

Realistic:

- Relevant, reasonable, rewarding and results-oriented

- Within the availability of resources, knowledge and time

To be realistic, a goal must represent an objective toward which mentor and mentee are willing and able to work. A goal can be both high and realistic; you are the only one who can decide just how high your goal should be. A high goal is frequently easier to reach than a low one because a low goal exerts low motivational force. Your goal is probably realistic if you truly believe that it can be accomplished.

Example:

Even if I do accept responsibility to pursue a goal that is specific and measurable, the goal won’t be useful to me or others if the goal is to “know how to work the desk during my first week”.

Time Based:

- Timely, tangible and trackable

- Enough time to achieve the goal

A goal should be grounded within a time frame. With no time frame tied to it, there’s no sense of urgency.

Example:

I want to learn to use the intravenous infusion pump on my unit. When do you want to have this skill mastered? “Someday” won’t work. But if you anchor it within a timeframe, 1 week, 2 weeks, set a specific date, and then you’ve set your unconscious mind into motion to being working on the goal. 14

Identify how you learn:

Knowledge of how one learns best will assist the mentor and mentee decide on strategies for learning.

Complete VARK (Visual, Aural, Reading/Writing, Kinesthetic) questionnaire on line and identify how one learns best.

Take this information to the first mentorship meeting as mentor and mentee embark on their mentoring journey.

Please complete: How Good a Listener Are You? [PDF] This tool assesses one’s ability to listen to others. If you identify that your listening skills require attention, it may encourage you to work on this ability.

It is important to assess the mentoring relationship often to insure that it is meeting the needs of both the Mentor and Mentee by:

- acknowledging the end of the mentoring relationship;

- having a closing strategy;

- discussing the difficulties in mentoring relationship; and

- understanding the reasons why mentoring relationships end prior to the 12 months.

Acknowledgement at the end of the Mentoring Relationship

Mentors should acknowledge and celebrate the mentee’s successful journey via both verbal and written expressions of appreciation. Verbal comments should be specific and focused on behaviours, for example:

- “I admire …”

- “You have a real knack for …”

- “I especially appreciated it when you …”

- Written notes from the mentor could offer a permanent record of support and encouragement as well as a memento. For example, the note could focus on:

- What you learned from your mentee

- An incident that has special meaning for you

- A motivational message for the future 15

Closing Strategy

A good closing strategy may consist of the mentoring partners discussing the following questions:

- What process did we follow to integrate? What was learned and how was that beneficial?

- What sources of evidence or best practices were used as a guide to inform the mentee’s practice in the future?

- Were there learning goals that were not thoroughly addressed? If yes, can they be addressed after the completion of the mentorship?

- How? By whom? Within what time line?

- Did we review and discuss issues of concern satisfactorily and on a regular basis?

- Were there mutual benefits within the mentoring relationship, and if so, in what way did we benefit?

- Have we decided on a meaningful way to celebrate the successes within the mentoring relationship?

- Have we had a conversation to discuss what direction our relationship could take?

- Has our conversation included talking about whether it will move from a professional mentoring relationship to colleagues, to friendship, to staying in contact and where to go from here?10

Difficulties in Mentoring Relationship

Zachary (2000) suggested that even when a mentoring relationship has developed problems, reaching a learning-focused conclusion can turn the whole experience into a positive one. The mentor could initiate a conversation with the following approaches:

- Acknowledge the difficulty without casting blame – for example, “It looks as though we’ve come to an impasse …”

- Consider what went right with the relationship as well as what went wrong – for example, “Let’s look at the pluses and minuses of our relationship so that we can each learn something from the process we have undergone.”

- Express appreciation – for example, “Although we haven’t been able to achieve all of your objectives, I think we were successful in one area. I attribute this success to your persistence and determination, characteristics which will be very helpful in your new job”.15

Reasons Why Mentoring Relationships End Prior to the 12 Months

Mentee “grows” beyond the boundaries of the relationship

When a mentee begins to gain more confidence and starts to perform more independently, the mentoring relationship may begin to wane. This is acceptable. You want your mentee to achieve independence and begin to make decisions independently. Of course, you and your mentee can still remain good friends and continue professional contact.

Mentor and Mentee have a "difference of opinion”

You may also find that the mentoring relationship is no longer beneficial to you or your mentee. Sometimes the mentoring relationship becomes exploitative and needs to be terminated. When a mentoring relationship ends, reflection and analysis need to be employed to discover why.

Both the mentor and the mentee should think carefully about whether their expectations were realistic and if their behaviours were appropriate. This reflection is beneficial if the mentor or mentee begins a new mentoring relationship with another individual.

Mentor or Mentee leaves position with Health PEI

A mentoring relationship can also end when one partner leaves their position. However, the role of advisor, counselor, teacher, or the other roles may still continue if both mentor and mentee wish to do so.

If either mentor or mentee require the termination of the relationship, attempts will be made to find a replacement.14

The Provincial Nursing Mentorship Program for New Graduate Nurses and Internationally Educated Nurses is developed to assist new graduate nurses and internationally educated nurses as they transition into the nursing workforce on Prince Edward Island. It provides the mentor with the satisfaction of supporting a new generation of nurses as they integrate into the workplace. The program content is intended to provide the mentor and mentee with a clear understanding of what a mentoring relationship is. It provides the resources to understand the transition process, and the tools to facilitate a successful relationship. According to CNA 2004, the benefits of a mentorship program are “improved quality of care, a sense of accomplishment and job satisfaction.” These benefits will result in the retention of nurses within the health care system on Prince Edward Island.

Congratulations - you've completed the Provincial Nursing Mentorship Program!

You must now complete the appropriate Evaluation Form and subsequent Nursing Education Certificate Request Form below.

Please complete the below evaluation that applies to you. This evaluation will assist with future revisions and updates to this program.

Upon completion of the evaluation, please complete the Nursing Education Certificate Request Form, so an e-certificate can be sent to you.

- Boychuck Duchscher, J. (2008). A Process of becoming: The stages of new nursing graduate professional role transition. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 39(10), 441-450. doi:10.3928/00220124-20081001-03

- Canadian Nurses Association. (2004). Achieving Excellence in Professional Practice. A Guide to Preceptorship and Mentorship. Ottawa. Canadian Nurses Association.

- DeSilva, B. (2009). Mentoring program enhances CM training. Health Care Benchmarks and Quality Improvement.

16(9) p. 99-102.

- Dyess, S. (2009). The first year of practice: new graduate nurses’ transition and learning needs. The Journal of Continuing Education, 40 (9), 403-410. doi:10.3928/00220124-20090824-03

- Faron, S., & Poelter, D.(2007). Growing our own. Inspiring growth and increasing retention through mentoring. Nursing for Women’s Health, 11(2), 139 – 143. doi:10.1111/j.1751- 486X.2007.00142.x

- Ferguson, L.M. (2010).From the perspective of new nurses: What do effective mentors look like in practice? Nurse Education in Practice, 11, 119-123. doi:1016/j.nepr.2010.11.003

- Fox, K.C. (2010). Mentor program boosts new nurses’ satisfaction and lowers turnover rate. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 4(1), 311 -316. doi:10.3928/00220124-20100401-04

- Fry, B. (2011). Thriving in the workplace: A nurse’s guide to intergenerational diversity. Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions. Retrieved from

http://neltoolkit.rnao.ca/sites/default/files/CFNU%20Thriving%20in%20Workplace.%20A%20Nurses%20Guide%20to%20Intergenerational%20Diversity.pdf

- Office of the Provincial Chief Nurse, Department of Health and Community Services, (2011). Cultural Awareness and Responsiveness Module for Mentors for Internationally Educated Nurses (IENs)”. Retrieved from https://www.med.mun.ca/nursingportal/default.asp

- Office of the Provincial Chief Nurse, Department of Health and Community Services, (2011). Mentorship: Nurses Mentoring Nurses Module. Retrieved from https://www.med.mun.ca/nursingportal/default.asp

- Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region.(n.d.) Mentoring Workshop Handbook for Protégés.

- Registered Nurses Professional Development Centre & Nova Scotia Department of Health (2011). Nova Scotia Mentorship Program. Department of Health, Halifax.

- Simpson, J.L. (2005). A Resource Guide for Implementing Nursing Mentorship in Public Health Units in Ontario.

Retrieved from http://neltoolkit.rnao.ca/sites/default/files/Caring_Connecting_Empowering_%20A%20Resource%20Guide%20for%20Implementing%20Nursing%20Mentorship%20in%20Public%20Health%20Units%20in%20Ontario.pdf

- Wong, A.T. & Premkumar, K. (2007). An introduction to mentoring principles, processes and strategies for facilitating mentoring relationships at a distance.

- Wortsman, A. & Crupi, A. (2009). From Text book to texting: Addressing issues of intergenerational diversity in the nursing workplace. Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions. Retrieved from

https://nursesunions.ca/research/from-textbooks-to-texting-addressing-issues-of-intergenerational-diversity-in-the-nursing-workplace-archived/

Disclaimer: Web links provided in this guide were current at time of printing.

| This project is funded in part by the Government of Canada's Foreign Qualification Recognition Program. |